—Andra Gillespie

I never thought I would say this, but I think I learned the lesson of the 2016 election on the streets of Newark, New Jersey a decade ago. It seems counterintuitive that an election that is being touted as the potential realignment of rural, white, working class voters to the Republican Party has any connection to a majority minority, overwhelmingly Democratic city. However, when I reflect on the class debates that are often the subtext of politics in Newark, I see strong parallels between the black nationalist populism of Newark and white working class populism that ushered Donald Trump into the presidency.

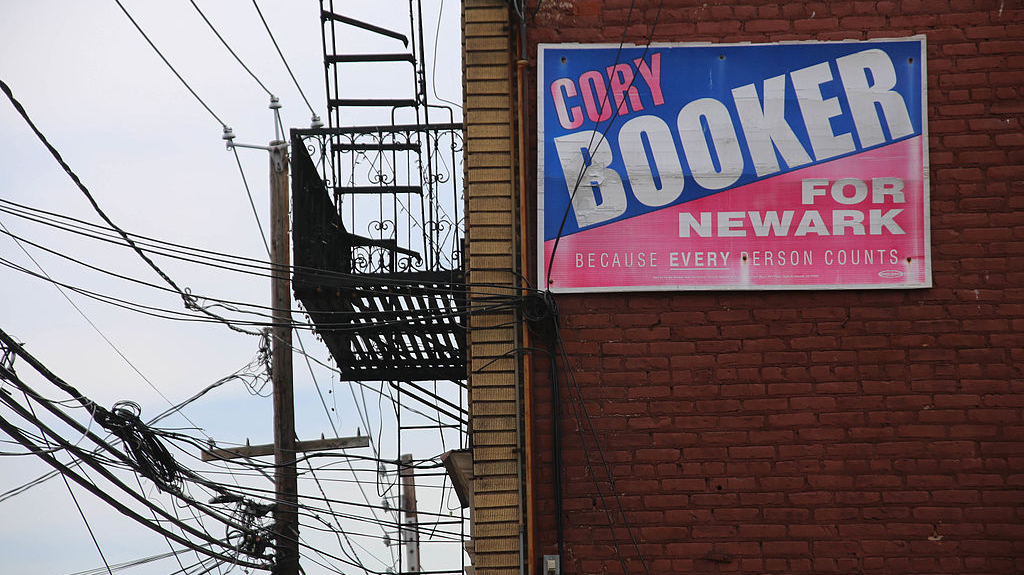

I met then Councilman Cory Booker fifteen years ago as he was planning to challenge Sharpe James for Newark’s mayoralty. I then talked my way into being allowed to do some voter turnout experiments on his campaign for my doctoral dissertation. While spending time in Newark setting up that experiment, I noticed the racial vitriol of that election cycle. Unlike our most recent election, the 2002 mayoral race pitted two black Democrats against each other in a quest to lead a city that was about 55% black. Booker ran as the young, telegenic, technocratic newcomer; James ran as the seasoned, consummate retail politician who appealed to black racial solidarity. The 2002 mayoral race was bare knuckled in its own way. Campaign signs were painted over or torn down, and Booker supporters complained that they were intimidated by the James machine if they dared go public with their support for Booker.

What was most fascinating in 2002 were the charges of racial authenticity. James was quick to paint Booker as an out-of-town interloper who did not understand Newark and would seek to gentrify the place. This argument quickly distilled into one of racial authenticity—in short, Booker was not black enough to be the mayor of Newark. It was not because Booker was light skinned and James was darker skinned, although the visual contrast reinforced the narrative James was trying to proffer. Rather “not black enough” became the catchall phrase for Newarkers who, among other things, were suspicious of Booker because he was a relative newcomer to the city, because he supported neoliberal policies like school choice, and because he garnered strong support from outsiders who they were convinced would seek to displace long-term residents from the city.

As my research project on Newark morphed from those initial field experiments to the ethnographic study that became my book, The New Black Politician, I had a chance to speak with many Newark insiders, both Booker supporters and detractors, about their impressions of Newark politics and Cory Booker’s leadership. I heard many things—some fair, some unfair; some thoughtful and some that were just completely outrageous and inflammatory. When I heard the inflammatory stuff, my first reaction was to discount it. However, I learned over time that what may sound crazy on the surface may have deeper meaning. I still may disagree with what these people were telling me; but as the researcher, it was my job to probe to gain a deeper understanding of what they were really trying to say—even if they did not have the “right” vocabulary to say it.

There are important applications to this recent election cycle. Through the institute I direct, I recently fielded a survey where I asked voters if they thought the election was rigged, an allegation that earned Donald Trump widespread and bipartisan criticism from elites every time he voiced this sentiment. Respondents who indicated that they did think the election could be rigged were allowed to define the various ways that they defined “rigged” (they were allowed to pick more than one type of rigging). I’m still going through the data (and have not yet weighted it), but respondents were 15 to nearly 25 percentage points more likely to define rigging in terms of media bias and the effects of money and special interests than they were to define it in terms of official manipulation or voter suppression. This just shows the importance of understanding what people say and what people mean.

If there is anything we can learn from this election, it is that we need to cultivate our deep listening skills. That Donald Trump’s populism won both the Republican primaries and the general election should be a wakeup call to all elites, regardless of their partisan or ideological orientation. There is a critical mass of Americans who are tired of know-it-alls dismissing their concerns and telling them why their ideas and policy preferences are stupid. They want to be heard, and though he was crass and offensive, Donald Trump told these folks that he was listening.

In many ways, the difference between elites and populists may be how we emphasize different aspects of representative democracy. Elites—pundits, technocrats, political operatives, college professors, etc.—tend to emphasize the representative aspect. This privileges the idea that there are natural divisions of labor based on expertise. Applied to politics, this implies that in matters of governance, citizens should defer to the smartest people in the room to set the agenda and to make decisions. Populists, though, emphasize the democratic part of representative government, implying that good ideas come from more places than the salons of the well-heeled and well-educated. And populists are more likely to emphasize democracy more when they feel that the technocrats dismiss their ideas or refuse to even try to understand what they’re saying.

To be sure, there are some policy ideas that are crackpot or unconstitutional. However, I think the lesson of this election cycle is that it takes more than a fancy résumé to earn the right to tell people that their ideas are unfeasible or crazy. One can more easily have that kind of conversation in the context of a relationship. Those relationships start with two-way conversations—not conversations where the “smart people” tell everyone else what to think, but where the smart people listen and learn from the experiences and perspectives of others. Not where we dismiss concerns offhand because the vocabulary seems unsophisticated, but where we seek to detect the nuance beneath the surface by asking more questions.

To some, this may seem like a capitulation to the base and, frankly, bigoted rhetoric that was a hallmark of this campaign cycle. I am by no means saying that we should excuse the abusive and discriminatory rhetoric that the president-elect used on his path to winning the presidency. However, we have to consider and understand the myriad concerns (racial and non-racial) that animated Trump supporters. The only way we are going to understand this is by talking to these people and taking a true interest in their perspective. We do not have to agree, but we do have to listen. And hopefully, once we prove that we can actually listen, then we contribute to a conversation that moves us toward consensus and away from the biased passions that inflame our politics and divide us in unhealthy ways.

Andra Gillespie is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Emory University and the author of The New Black Politician: Cory Booker, Newark, and Post-Racial America (NYU Press, 2013).

Andra Gillespie is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Emory University and the author of The New Black Politician: Cory Booker, Newark, and Post-Racial America (NYU Press, 2013).

Feature image:Because Every Person Counts by Paul Sableman. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.