—Martin Joseph Ponce

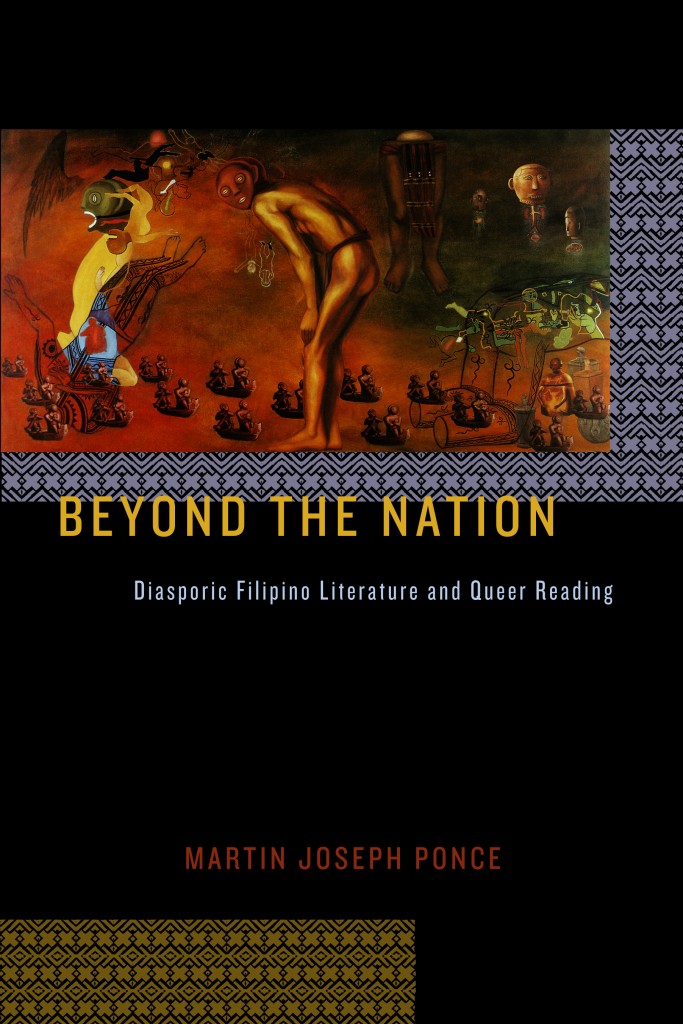

Broadly speaking, my book Beyond the Nation: Diasporic Filipino Literature and Queer Reading provides a history of Filipino literature in the United States from the onset of U.S. colonialism in the Philippines at the end of the nineteenth century through the contemporary moment. Framing the literature in a transnational context shaped by U.S. (neo)colonialism and migration, it focuses in particular on the ways that gender and sexuality are integral to Filipino racializations, social formations, and state and cultural nationalisms as well as to manifestations of U.S. empire and terms of assimilation at specific historical junctures.

Broadly speaking, my book Beyond the Nation: Diasporic Filipino Literature and Queer Reading provides a history of Filipino literature in the United States from the onset of U.S. colonialism in the Philippines at the end of the nineteenth century through the contemporary moment. Framing the literature in a transnational context shaped by U.S. (neo)colonialism and migration, it focuses in particular on the ways that gender and sexuality are integral to Filipino racializations, social formations, and state and cultural nationalisms as well as to manifestations of U.S. empire and terms of assimilation at specific historical junctures.

Although I discuss the work of several writers who self-identify as gay or queer and consider the depictions of queer characters in various literary texts, the book as a whole doesn’t seek to document a history of non-normative Filipino sexualities or desires in literature. Rather, it attempts to theorize and enact a queer reading practice that attends to the constitutive articulations of gender, sexuality, and eroticism to race, nation, and diaspora. As such, it would seem to bear a tangential relation, at best, to Gay Pride.

Indeed, insofar as the book seeks to contribute to the growing, diverse bodies of scholarship associated with queer of color and queer diasporic critique, it is less concerned with the development and consolidation of sexual identities than with the gendering and sexualization of race (Filipinos/as as savage, effeminate, hypersexual, hyperfeminine) and with the freighted political meanings that gender and sexuality assume when placed in comparative international contexts (liberation vs. repression, modern equality vs. patriarchal hierarchy). Both of these historically shifting but persistent conditions—the production of racial difference in part through gender and sexual deviance from white colonial norms, the production of U.S. exceptionalist discourses in part through (illusory) ideals of gender equality and sexual freedom—place diasporic Filipino writers in vexed positions. Namely, they must contend simultaneously with imperialist denigrations of colonial bodies and aptitudes as well as with nationalist recuperations of normative bodies and aspirations.

However distant they may seem, these ideas come to mind when I think of Gay Pride. While I imagine that for many LGBTQ folks the revelries represent a unique time of the year when all manner of things queer are welcomed, encouraged, and (dare I say it) rendered normal, I tend to see and experience the event as a discomfiting moment when the racialization of non-normative sexualities comes to the surface. Or put conversely, it is when every Pride participants’ sexuality is up for grabs and the default straightness of everyday life is suspended that racial differences and the ambiguous, deviant sexualities they signify become all the more apparent.

Moreover, the specific circumstances that enabled the emergence of Gay Pride in the first place and that we’re supposedly (supposed to be?) commemorating—Stonewall, the Village, New York, the Sixties, and so on—leave me wondering if these particularities are being strategically forgotten or rewritten by the Gay Prides taking place throughout the country and around the world. To avoid further entrenching the association of “modern” gayness with white U.S. sexceptionalism, metronormativity, and capitalist entertainment spectacles, I can only hope that this annual event is being remade dozens of times over, cross-cutting global gay and lesbian imaginaries and practices with local histories and politics, demographics and desires, fabulosities and festivities.

Martin Joseph Ponce is Associate Professor of English at The Ohio State University.

»» Happy Pride from NYU Press! Save 25% on a selection of our new and classic LGBT Studies titles, when you order via our website. Sale ends on July 1, 2013.