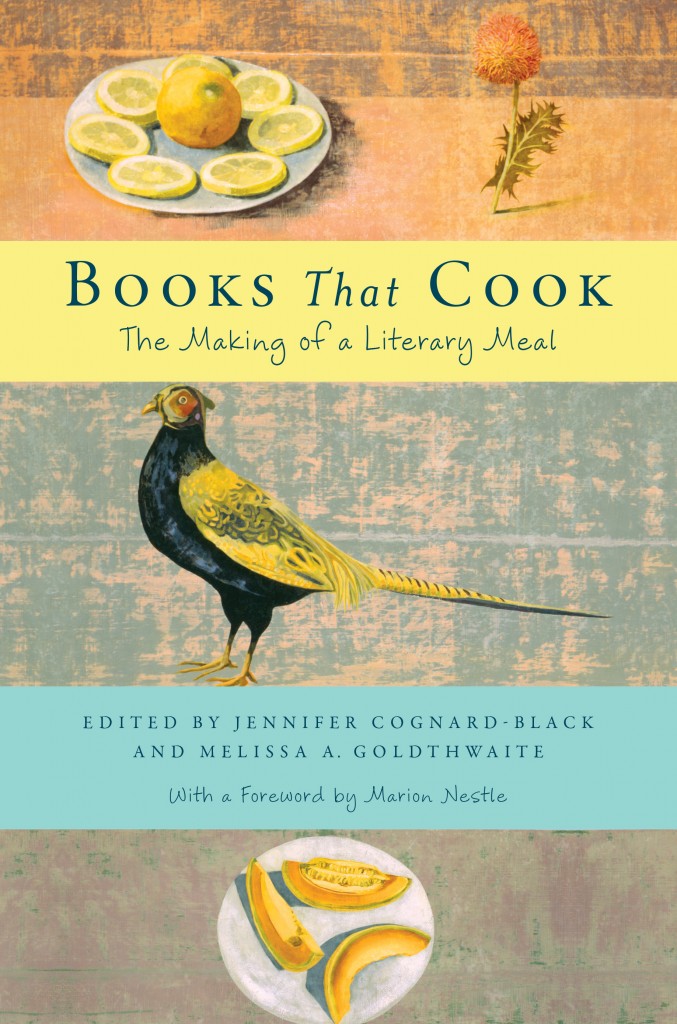

During the month of September, we’vee celebrated the publication of our first literary cookbook, Books That Cook: The Making of a Literary Meal by rounding up some of our bravest “chefs” at the Press to take on the task of cooking this book! Check out the reviews, odes, and confessions from Press staff members who attempted various recipes à la minute.

During the month of September, we’vee celebrated the publication of our first literary cookbook, Books That Cook: The Making of a Literary Meal by rounding up some of our bravest “chefs” at the Press to take on the task of cooking this book! Check out the reviews, odes, and confessions from Press staff members who attempted various recipes à la minute.

Our final post comes from Monica McCormick. Read below as she shares her thoughts on finding home through the joy of cooking.

I have moved often in my adult life. In each new apartment, preparing meals has become a way of making a home. Pulling out my well-used pots and knives, reaching for ingredients in strange new cupboards, and learning the quirks of an unfamiliar stove are all part of the ritual. Whatever I cook, it fills my new place with comforting scents and flavors, evoking other meals in other homes, long ago.

The opening lines of Ketu H. Katrak’s essay evoked this nostalgia created by food, sounds, and scents.[1] She writes of waking in her childhood home in Bombay on a visit from the U.S., roused from sleep by clanging in the kitchen:

All these sounds mingle with the aromatic spices wafting over my waking body. The sounds of prayer and smells of chapatis and vegetables weave into a pattern of belonging, of home-sounds and home-aromas.

This brought me back to a related, though in some ways opposite, experience. At age 18, I left Stockton, California, for a year as an exchange student in Mombasa, Kenya. I have often thought of my first few mornings there, waking to strange sounds and smells: voices shouting (in what language?), a rooster crowing, the cranking of an old car engine that wouldn’t turn over, foods frying in an oil I couldn’t identify, the oddly floral soapy water my host sister was sloshing on the hallway floor. I wondered how I would ever feel comfortable with all this.

I found my way home there through the kitchen. My host family, like my California one, made meals a central daily ritual. The Oderos were Luo people from Lake Victoria in western Kenya, but in Mombasa they cooked in the Swahili style. This Indian Ocean culture was wholly new to me, combining people and traditions from places like Zanzibar, Goa, Gujarat, Oman, and the Seychelles on the East African coast. I learned to roll out flaky chapatis, though my first attempts were so far from round that my sister Leonida would laugh, “It’s the shape of Kenya!”

I grated coconut, seated on a low folding stool fixed with a serrated blade, the white flakes falling to a plate below. We packed the coconut in a long, cylindrical basket and twisted it to extract the milk that thickened stews of fish, potatoes, tomato, and curry spices, or flavored large pots of long-grained basmati rice. I pounded the tiny red chilies that grew outside our back door, burning my fingers as I scooped the paste out of the big wooden mortar and pestle.

Eventually I took on the family task of going to the covered open-air market, mixing my minimal Kiswahili with English to bargain for staples: potatoes, onions, tomatoes, rice, beans, lentils, and the local bananas, mangos, and papayas. At my favorite stand was a corpulent yet dignified man in a white skull cap, presiding over trays mounded with brilliant-colored spices: cumin, coriander, turmeric, cayenne, paprika, mustard seeds. From his high stool he would reach out to scoop what you needed on to a metal scale, blending to your specifications, and pouring the spices into newspaper cones, twisted at the ends.

At school, we had a two-hour lunch break. Because my host family lived a long bus ride away, schoolmates would bring me to home with them. I especially loved invitations from Bansari Shah, a girl whose tiny frame belied her healthy appetite. Her mother seemed to spend all morning preparing our lunch, in a kitchen lined with shiny metal tins of lentils, grains, and spices. She would set out a gorgeous array of vegetarian dishes: okra stewed with tomato and chili; acid-yellow turmeric potatoes flecked with black mustard seeds; green mung-bean dal; shiny white rice studded with cloves and cardamom pods. Bansari pointed out her favorites to be sure I tried them, and we would tuck in happily.

When I returned to the States, I was homesick for Mombasa. I made some of this food, trying to reproduce the methods and tastes in American kitchens. Like Ketrak in Massachusetts, I found Indian grocers in Minneapolis and San Francisco where I could once again inhale the combined scent of innumerable spices, and select from bins of lentils, dried peas, and beans. I bought Indian cookbooks and made elaborate meals with many garnishes. It was all a lot of work, and over the years I’ve simplified my cooking.

But Katrak’s recipe for Yellow Potatoes reminded me of lunch with Bansari. It inspired a trip to the Indian markets on Lexington Avenue near East 29th Street. I selected fresh packets of turmeric and black mustard seeds, and asked the grocer to reach me a bunch of cilantro, a knob of ginger and a lime from the small cooler behind the counter. Back in my little Harlem kitchen, I heated a generous slug of oil in my favorite heavy pot, let the mustard seeds pop to season the oil, and sizzled cubes of potato with the spices and minced chilies. When the potatoes were tender, I added a squeeze of lime, a few torn cilantro leaves, and gave a quick stir. Breathing in the flowery, sharp, tangy aromas, I took a mouthful and felt right at home.

Monica McCormick is Program Officer for Digital Scholarly Publishing at NYU Libraries and NYU Press.

[1] Food and Belonging: At ‘Home’ and in ‘Alien-Kitchens’, by Ketu H. Katrak