In Brooklyn’s Promised Land, historian Judith Wellman sheds light on the virtually lost history of Weeksville, an independent free black community in nineteenth-century Brooklyn.

In Brooklyn’s Promised Land, historian Judith Wellman sheds light on the virtually lost history of Weeksville, an independent free black community in nineteenth-century Brooklyn.

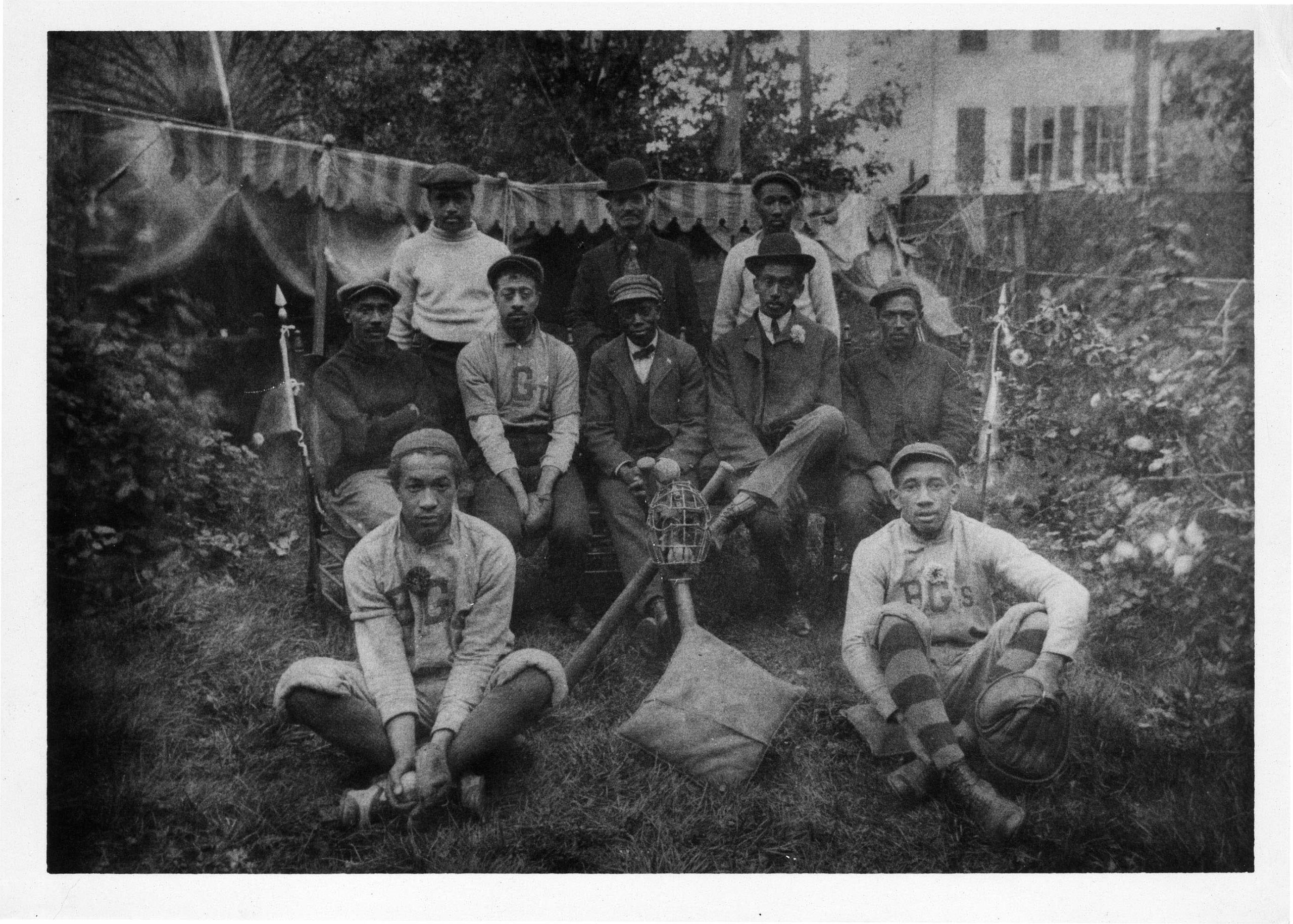

Founded after slavery ended in New York State in 1827, Weeksville provided a space of safety, prosperity, education, and even power. Its residents owned property, set up their own churches, established two newspapers, and even created a baseball team, appropriately named the Weeksville Unknowns.

In the interview below, Wellman discusses her research for the book, Weeksville’s most remarkable features, and the national significance of this extraordinary place.

Q: Why is Weeksville important?

Judith Wellman: Through the lens of Weeksville as a unique community, we see how real people dealt with national events and movements in African American and American history. Formed at the end of slavery in New York State, Weeksville was a reaction to the attempt to send free people of color to Africa. Its citizens were involved in virtually every movement for African American rights in the nineteenth century, including the black convention movement, voting rights, Underground Railroad, Civil War and Reconstruction, and the emergence of Progressive reform. Weeksville’s success transcends its unique local history and makes it an important model for the world.

When and how did you first come across the space of Weeksville?

In the early 1980s, I was working with a National Park Service Ranger named Stephanie Dyer. Stephanie lived in the Bronx, but she and I were both working at Women’s Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls, New York. When I visited Stephanie in New York, I thought we were going to visit the Teddy Roosevelt birthplace, but Stephanie took me instead to Weeksville. I’ll be forever grateful for that. And I’ll never forget my first sight of Joan Maynard, founding director, coming down the narrow staircase of one of the old houses on Hunterfly Road, now owned by the Weeksville Heritage Center. I have been hooked ever since!

Your study relies mostly on public sources instead of private manuscripts. Could you say more about these materials?

So few early Weeksville residents wrote specifically about their own experiences that we began to look for every public record we could find. Census records recorded (or at least attempted to record) the names of all U.S. residents, including those in Weeksville. They gave us vital information about race, age, sex, occupation, literacy, and property ownership of Weeksville residents. They also gave us names, which we used to look up deeds, assessment records, genealogical materials, and newspaper accounts. Newspapers, especially the Brooklyn Eagle, online through the Brooklyn Public Library, provided invaluable details. So did numerous maps. Most unexpectedly, we also found many images relating to Weeksville’s houses, institutions, and people.

This book includes forty-two images and six maps, to give readers a sense of Weeksville as a real place. Wherever possible, it also includes direct quotations from Weeksville’s residents, so readers can hear real voices.

You described your approach as both chronological and topical. Which period between 1770 and 2010 would you consider to be the most representative or most important in Weeksville’s development?

I most enjoyed learning about Weeksville in the two decades before the Civil War, when it was first founded and grew. By 1855, 521 people lived in Weeksville. Eighty-two percent of them were African Americans. It was a cosmopolitan community, attracting people from the eastern U.S. (including New York, Pennsylvania, Washington, D.C., South and North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland) and also from the West Indies and Africa.

Although only the school principal—Junius C. Morel—was nationally known before the Civil War, Weeksville was home to a variety of remarkable people, including Francis P. Graham, “a man of many eccentricities,” as noted by the New York Times, who was accused of participating in the Denmark Vesey rebellion in Charleston, South Carolina in 1822, went to Liberia, and then returned to New York City. He later became a minister, shoemaker, and the largest resident landowner in Weeksville. His nephew (or perhaps his natural son), James LeGrant, became Weeksville’s only carpenter. James LeGrant married Lydia Ann Elizabeth Simmons LeGrant, one of only four women in Weeksville who owned land. All of these people and more lived on the block just north of the current Weeksville Heritage Center house, where the Kingsborough housing project now stands.

How was this community rediscovered in 1966? Was there any historical reason behind this rediscovering moment?

Weeksville was rediscovered in the context of the civil rights and black power movements of the 1960s. Major credit for this rediscovery goes to Jim Hurley, formerly an aerial photographer with the U.S. Navy and Vice Consul to Pakistan. In the mid-1960s, Mr. Hurley was giving tours of New York City neighborhood through the Museum of the City of New York. In 1968, he offered a noncredit workshop through the Pratt Institute of Community Development called “Exploring Bedford-Stuyvesant and New York City.” Delores McCullough and Patricia Johnson were students in this course, and they focused on Weeksville. This group identified the old Hunterfly Road. Then Joseph Haynes, an engineer for the Transit Authority and a professional pilot, took Jim Hurley on a flight to take photos of the old landscape.

The following year, in 1969, the Model Cities Redevelopment Program decided to demolish several old houses near the corner of Dean Street and Troy Avenue. Local residents, including William T. Harley, students from P.S. 243, and Boy Scouts from Troop 342 worked with Jim Hurley, who had a small grant to retrieve objects from these houses before they were demolished. Among other items, they found a Revolutionary War-era cannonball (Weeksville was on the pathway of British troops who came to Long Island) and a tintype of woman who came to be known as the Weeksville Lady.

Local supporters organized Project Weeksville to continue this research. Barbara Jackson worked with students in P.S. 243; Robert Swan did detailed research; Loren McMillan and students from P.S. 243 convinced New York City to designate Weeksville as a landmark. Joan Maynard became Director of the new Society for the Preservation of Weeksville and Bedford-Stuyvesant history, bringing this grassroots preservation effort to national attention. And the rest, as they say, is history.

What are the most remarkable features of Weeksville?

Weeksville was a success story. So often we hear about the horrors of slavery and the difficulty of African Americans surviving as free people of color. All of this is important. We need to know this. But if we focus not on what people in the dominant culture did to (or for) African Americans and highlight what African Americans did for themselves, we often find a very different, much more positive story.

This book highlights the experience of ordinary people who together created an extraordinary community—a place of physical safety, high levels of property ownership (about thirty percent of adult men owned property), political participation, education and literacy (with a 93 percent literacy rate for young adults in the 1860s), and the development of community institutions (two churches, a school, an orphan asylum, and a home for the aged) that ultimately formed an important grassroots basis of social reform—the Progressive movement—in the early 20th century.

By the 1850s and 1860s, they had attracted the attention of nationally known African American leaders. People such as Martin Delany, Henry Highland Garnet, and Rufus L. Perry made Weeksville the headquarters of the African Civilization Society (designed to set up communities of free people in West Africa). Maritcha Lyons made a career as an assistant principal in the Weeksville school, the first person in the U.S. to mentor both African American and European American student teachers together. Susan Smith McKinney Steward, daughter of one of Weeksville’s early landowners, became an early woman doctor.

One of Weeksville’s most noticeable features is that the whole village was dramatically changed—virtually wiped out—by the expansion Brooklyn’s street grid after completion of the Eastern Parkway and Brooklyn Bridge in the 1870s and 1880s. Today, only a very few of Weeksville’s pre-Civil War buildings remain, including the ones on Hunterfly Road, now owned by the Weeksville Heritage Center.

How does remembering Weeksville shed light on the future of African American communities and our society at large?

Weeksville’s citizens wanted to make real in their own lives the American ideal that all people are created equal. Ironically, to fulfill this dream, they had to move to a place outside the control of the dominant culture. As one of about one hundred African American intentional communities before the Civil War, Weeksville fulfilled its goals as a place of safety, property ownership, education, and employment for its residents.

The residents of Weeksville formed a unique community in a unique time and place, but their message transcends that uniqueness to speak to us all, as citizens of this world in the early 21st century. Specifically, Weeksville challenges us as citizens of this world to consider the usefulness of separatism versus integration as a way to create places of respect and empowerment for all people.

As a historian of European American background, how did you become involved in the project?

This project actually started out as a National Register nomination, not a book. In 2003, Pam Green, Director of the Weeksville Heritage Center, invited me to work with them on a National Register nomination for the Weeksville houses. We had a wonderful team of people—Cynthia Copeland, Judith Burgess-Abiodun, Theresa Ventura, Lee French, Victoria Huver, and others—with everyone working on different sources. We were all astounded by how much we found. The project kept growing, until it finally became this book.

Truly, in so many ways, I am an outsider to Weeksville. I did not grow up in Weeksville. I did not grow up in any African American community. So there is much that people who grew up there would instinctively know but about which I am completely unaware.

Yet, by their success, the people of Weeksville transcended their own small unique community. They spoke to Americans—white as well as black—across the country, today as well as in the nineteenth century. We all—as citizens of this world—need to know their stories, so that we can learn something from them.