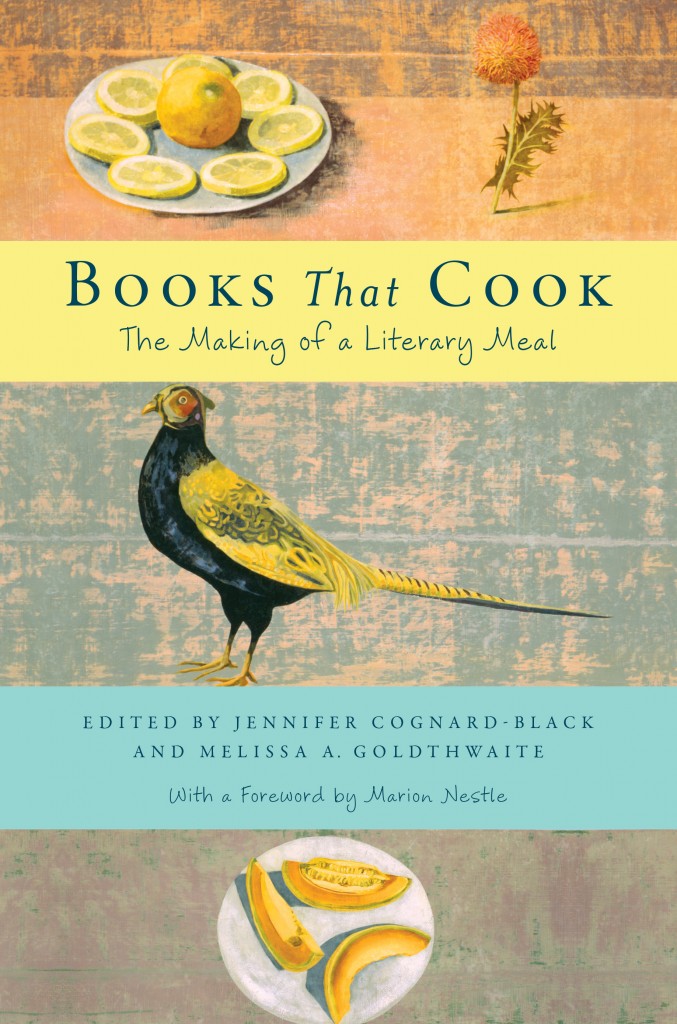

During the month of September, we’re celebrating the publication of our first literary cookbook, Books That Cook: The Making of a Literary Meal by rounding up some of our bravest “chefs” at the Press to take on the task of cooking this book! In the next few weeks, we’ll be serving up reviews, odes, and confessions from Press staff members who attempted various recipes à la minute.

During the month of September, we’re celebrating the publication of our first literary cookbook, Books That Cook: The Making of a Literary Meal by rounding up some of our bravest “chefs” at the Press to take on the task of cooking this book! In the next few weeks, we’ll be serving up reviews, odes, and confessions from Press staff members who attempted various recipes à la minute.

Today, editorial assistant Constance Grady shares her thoughts on “A Good Roast Chicken,” an essay featured in the book from professional chef and food historian Teresa Lust.

Roast chicken is a good dinner for many reasons. It is economical: a decent-sized bird is a good meal for a family of four, with enough left over for some sandwiches or perhaps a pot pie, and then you can turn the bones and giblets into stock for soup or a risotto. It is forgiving. You can buy a free-range organic bird from a farmer’s market for an ungodly sum, and then massage a compote of herbs and butter under its skin and stuff it with more herbs and garlic and lemon, and baste it with melted butter as it roasts, and flip it halfway through cooking so that the juices are evenly distributed through the whole chicken. This will be good. You can also buy a five-dollar bird from the supermarket and spritz it perfunctorily with Pam, perhaps shaking some table salt and pre-ground pepper over the skin, and stick it in the oven and forget about it for two hours. This will also be pretty good.

It is also—and this is probably what is most attractive about roast chicken for many of us—simple. Even a gussied-up roast chicken is quick and easy to prepare; it will allow you to put a full meal on the table with a minimum of labor. But what Teresa Lust reminds us in “A Good Roast Chicken” is that roast chicken is not an intrinsically easy dish: it’s just that we’ve outsourced the labor.

Lust is the granddaughter of farmers, and she describes in detail all of the dirty, uncomfortable farm work that goes into a roast chicken. Someone has to break the chicken’s neck. Then the chickens have to be dipped into boiling water to loosen their feathers, and plucked. The feathers that don’t come out with plucking have to be singed off, or alternatively, waxed off like unruly eyebrow hair. Then, of course, they have to be beheaded and de-feet-ed and gutted, and now at last we come to something resembling the chicken that you pick up in paper wrappings at the farmer’s market or in plastic shrinkwrap at the grocery store.

Lust does not mourn for the farm life of her grandparents. “I am not so sentimental,” she writes. I have the same attitude: I do not especially feel deprived at having never smelled chicken feathers scorching as I burn them off a partially plucked carcass. But it is good to be reminded that the food we take for granted is the product of immense industry, and that the “raw ingredients” we buy at the grocery store are anything but.

Lust’s recipe is a good balance between the easiest and the most elaborate versions of roast chicken. You rub the skin down with melted butter or olive oil, and stuff the cavity with herbs and garlic and lemon. Then you let it sit in a hot oven for an hour. Previously I have been wedded to the system of using a very hot oven for the first ten minutes to sear the skin, and then turning the temperature down for a long, slow roast, but I think Lust’s method is better. The skin comes out crisp and brown, and the meat is succulent and moist.

Lust serves her chicken with buttered carrots and parslied new potatoes. This is simple and pleasant, but I decided instead to roast the chicken on a bed of vegetables. On this I refuse to compromise: cooked this way, the vegetables caramelize and are permeated with the rich flavorful juices of the chicken, so that even celery becomes delicious. Also it saves on dishes, because the entire meal is cooked in your roasting pan. I used carrots and celery and onions and potatoes and garlic, but you can use any vegetable that catches your fancy. Zucchini is good in the summer, and so is asparagus. I am told that a bulb of fennel is a welcome addition, if you like fennel (I do not), and leeks add a nice earthiness.

Cooking this chicken, you are most likely far from the life Lust describes, “a life full of vegetable gardens and barnyards and meals rushed from the farm to the table,” and “a life where there’s no denying that what lies succulent and crisp on a bed of rosemary sprigs once scratched in the dirt.” The beauty and power of her essay is that it brings this life back to us: it reminds us of the labor embodied in the carcass of a chicken.