—Christel Manning

It has become almost a truism that religion is central in American elections. It’s not just the Republicans who needed the Evangelical vote to win. Even Democrats reliably trot out their religious credentials at election time. If you believe in God, attend church or synagogue, and claim to pray for those afflicted by tragedy, it is supposed to demonstrate that you are a moral and therefor trustworthy candidate. But that seems to be changing—at least in this year’s election.

It has become almost a truism that religion is central in American elections. It’s not just the Republicans who needed the Evangelical vote to win. Even Democrats reliably trot out their religious credentials at election time. If you believe in God, attend church or synagogue, and claim to pray for those afflicted by tragedy, it is supposed to demonstrate that you are a moral and therefor trustworthy candidate. But that seems to be changing—at least in this year’s election.

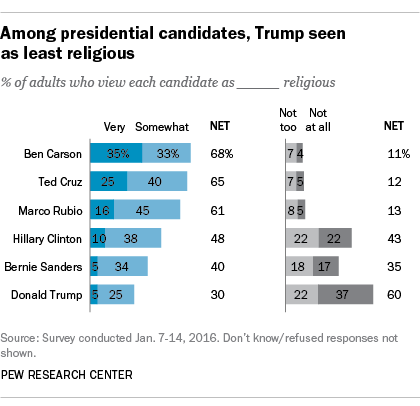

First, Americans as a whole are becoming less religious. Recent polls show a continued decline in religiousness as measured by belief in god, prayer, church attendance. Twenty-five percent of adults now claim NO religion. The proportion of so called religious “Nones” has increased among all age groups but especially the young: one third of adults 18 – 30 are Nones. Less religious voters are obviously going to care less about a candidate’s religion. But even among religious voters, religion seems to matter less. Trump is getting wide support from Evangelicals, despite the fact that most Republican voters see him as non-religious or not-very religious. Although 51 percent of Americans still say they are less likely to vote for an atheist, that percentage has declined from 63 percent in 2007.

Why this change, and what does it mean for election 2016? One obvious explanation is that economic issues have, pardon the pun, trumped social and religious ones. When Americans are angry because jobs are going to Mexico and China, they can’t pay their college debt, and terrorist attacks seem looming everywhere, preventing abortion or promoting gay marriage (depending on which side you’re on) slips down the priority list. Nones are the most reliable constituents for the Democrats, and Evangelicals for the Republicans, but religion does not seem to be a motivating either of them.

There is also a bigger generational change going on. Younger voters, be they right or left leaning, are not following the party line of what religion is supposed to mean. They are more open and tolerant and flexible than their parents were on many issues. Many young Nones are not atheists; rather, they decline to claim a religion because they don’t want to follow a particular doctrine, they want to pick and choose their own spirituality from a variety of different sources that may include mindfulness meditation, walks in nature, and the occasional church visit with family. By the same token, young Evangelicals may be committed to Christ but they interpret this in their own way, including greater support for LGBT rights and environmentalism, issues their parents and their conservative churches have ardently opposed. Indeed, some young Evangelicals actually identify as Nones—because they reject how political organized religion has become. In short, being a None, whether you are secular or an unchurched believer, is an assertion of rejecting established organizations.

In my own research on Nones who become parents, I found that they are disinclined to affiliate with any organization unless they feel embattled. For example, atheist parents living in the Bible Belt will be more motivated than those living in New England to provide their kid with a humanist Sunday school or get involved in the PTA to prevent a creationist curriculum. But being non-religious is becoming increasingly accepted in America, so it isn’t what drives elections.

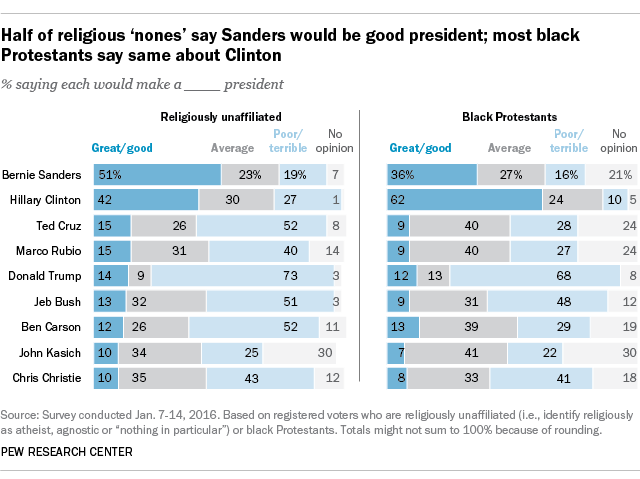

A recent Pew poll shows most Nones going for Bernie Sanders (51%) and disliking Donald Trump (73%). This is consistent w. Sanders’ appeal among younger voters, who are much more likely to be Nones. But Bernie supporters are not motivated by their lack of religion. They are motivated by passion and anger about the economy, just like Trump voters are. Trump is a chameleon. He has taken political positions that lean both left (anti-trade) and right (anti-immigration); he’s neither overtly secular nor religious; and he easily changes his message to suit a particular audience. So his supporters can project onto him whatever they want. In the general election, he’s likely to soft pedal his extremer views in order to reach the independent vote, and we all know how short voters’ memory can be. The Democrats need the Nones to win this election, but young Nones do not like establishments. If Sanders fails to win the nomination, and Trump presents a more tolerant face than he did in the primaries, the None vote may be harder to predict than we think.

Christel Manning is Professor of Religious Studies at Sacred Heart University (CT). She is the author of Losing Our Religion: How Unaffiliated Parents Are Raising Their Children (NYU Press, 2015).