—James Joseph Dean

The kaleidoscope of straight masculinities may be seen through shifts and changes in everyday language, fashion, and style. In American and British contexts, straight men’s identity practices negotiate a post-closeted culture, which I define as the presence of openly gay and lesbian individuals and representations of LGBTQ people. This post-closeted culture pressures straight men to be more tolerant of gays and to express less vitriolic forms of homophobia, while, at the same time, it conditions and supports gay-friendly straight men’s non-homophobic and anti-homophobic expressions.

It is in post-closeted cultural contexts where phrases like “no homo” emerge and gain meaning. For me, the phrase “no homo” signals less a homophobic attitude and more a way of flagging one’s straight status and claiming its privilege. “No homo” is an anxiety-driven way of saying, “What I said might come off as gay, but I’m really straight.”

It is in post-closeted cultural contexts where phrases like “no homo” emerge and gain meaning. For me, the phrase “no homo” signals less a homophobic attitude and more a way of flagging one’s straight status and claiming its privilege. “No homo” is an anxiety-driven way of saying, “What I said might come off as gay, but I’m really straight.”

On the website Urban Dictionary, for example, “no homo” is defined as a “phrase used after one inadvertently says something that sounds gay.” The example given to illustrate the definition is: “His ass is mine. No homo.” The phrase aims to indicate that the intended statement was not meant to imply a homosexual sexual desire or a gay identity.

Although the phrase “no homo” emerged out of hip hop music in the early 2000s, as language scholar Joshua Brown and journalist Jonah Weiner have explained, it continues to live on in the everyday talk of American youth. Alongside but qualitatively less homophobic than the epithet “fag,” “no homo” aims to reclaim straight status and privilege but avoid the hatefulness of the fag discourse, which as sociologist C.J. Pascoe shows is about both boys policing other boys’ masculinities and their homophobic prejudice.

At its best, “no homo” signals a non-homophobic stance that aims neither to be prejudicial nor against gay prejudicial attitudes. Rather, it is an interjectory phrase that reflects a way straight masculine culture manages its status in a post-closeted culture, where an anxiety over coming across as gay looms in a seemingly omnipresent way. At its worst, “no homo” is used as a homophobic insult along the lines of “fag,” acting as another weapon to police expressions of masculinity and sexuality.

While “no homo” is a linguistic innovation of everyday language, metrosexuality represents a style and consumption practice, where straight and gay men share and trade on the social status they receive for displaying fashionable styles and having well-groomed appearances. Coined in 1994 by journalist Mark Simpson, the term continues to circulate as an entry point into the style practices of fashionable straight men.

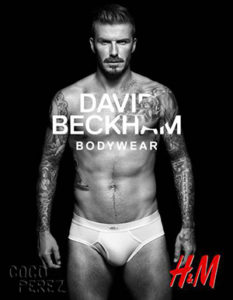

The global icon for metrosexuality is David Beckham. No longer a soccer player, bending it like Beckham today probably means buying his underwear line from H&M. Another contender for his metrosexual fashion appeal might be Kanye West, who sports kilts in concert, is an outspoken critic of homophobia, and helped popularize “no homo” in his collaboration on Jay-Z’s song “Run this Town.” Keeping straight men like Beckham and West in mind, the term metrosexual is a loose label that refers to straight men who adopt style, beauty, and consumption practices associated with gay men and women.

The global icon for metrosexuality is David Beckham. No longer a soccer player, bending it like Beckham today probably means buying his underwear line from H&M. Another contender for his metrosexual fashion appeal might be Kanye West, who sports kilts in concert, is an outspoken critic of homophobia, and helped popularize “no homo” in his collaboration on Jay-Z’s song “Run this Town.” Keeping straight men like Beckham and West in mind, the term metrosexual is a loose label that refers to straight men who adopt style, beauty, and consumption practices associated with gay men and women.

In my book Straights: Heterosexuality in Post-Closeted Culture, I interviewed a diverse group of straight men about their thoughts on metrosexuality. Did they consider themselves metrosexuals? How so? If not, what did they think of metrosexual men? For some of the straight men I talked to metrosexuality was a label that others applied to them or that they took on in jest. Due to wearing stylish clothes, having a well-groomed appearance, and exhibiting a more relaxed masculinity, the metrosexual men I interviewed enacted a more fluid gender presentation than many of the non-metrosexual men in the study.

Their metrosexual masculinity also conditioned their ease in socializing in mixed gay/straight spaces as well as predominantly gay ones. Not surprisingly, their social circles included straight women and lesbians, straight men and gay men, among others. The audiences for metrosexual men’s performances were largely supportive of their non-homophobic and gay-friendly stances, admired their confidence, and appreciated their beauty.

Sociologically, metrosexuality represents a blurring of straight and gay identity practices and styles, enlarging the way men, straight and gay, may perform their masculinity in everyday life. The potential drawback of metrosexual masculinity is its recuperation into another dominant masculinity of, say, only upper class straight men, or in it becoming a masculinity that anxiously marks itself as strictly straight. As in: “Metrosexual. No homo.”

James Joseph Dean is Associate Professor of Sociology at Sonoma State University and author of Straights: Heterosexuality in Post-Closeted Culture (NYU Press, 2014).