—Kerry Mitchell

Park rangers have a trick for getting people to follow the rules: it’s called the Authority of the Resource Technique (ART). Rather than simply tell people what the rules are, rangers will explain how a natural resource is protected by the rule and threatened by people breaking it. The idea is to tap into people’s respect for nature and their desire to preserve it, rather than simply relying on their respect for authority. Unfortunately, the technique doesn’t always work, even when the resource being protected is the visitors themselves.

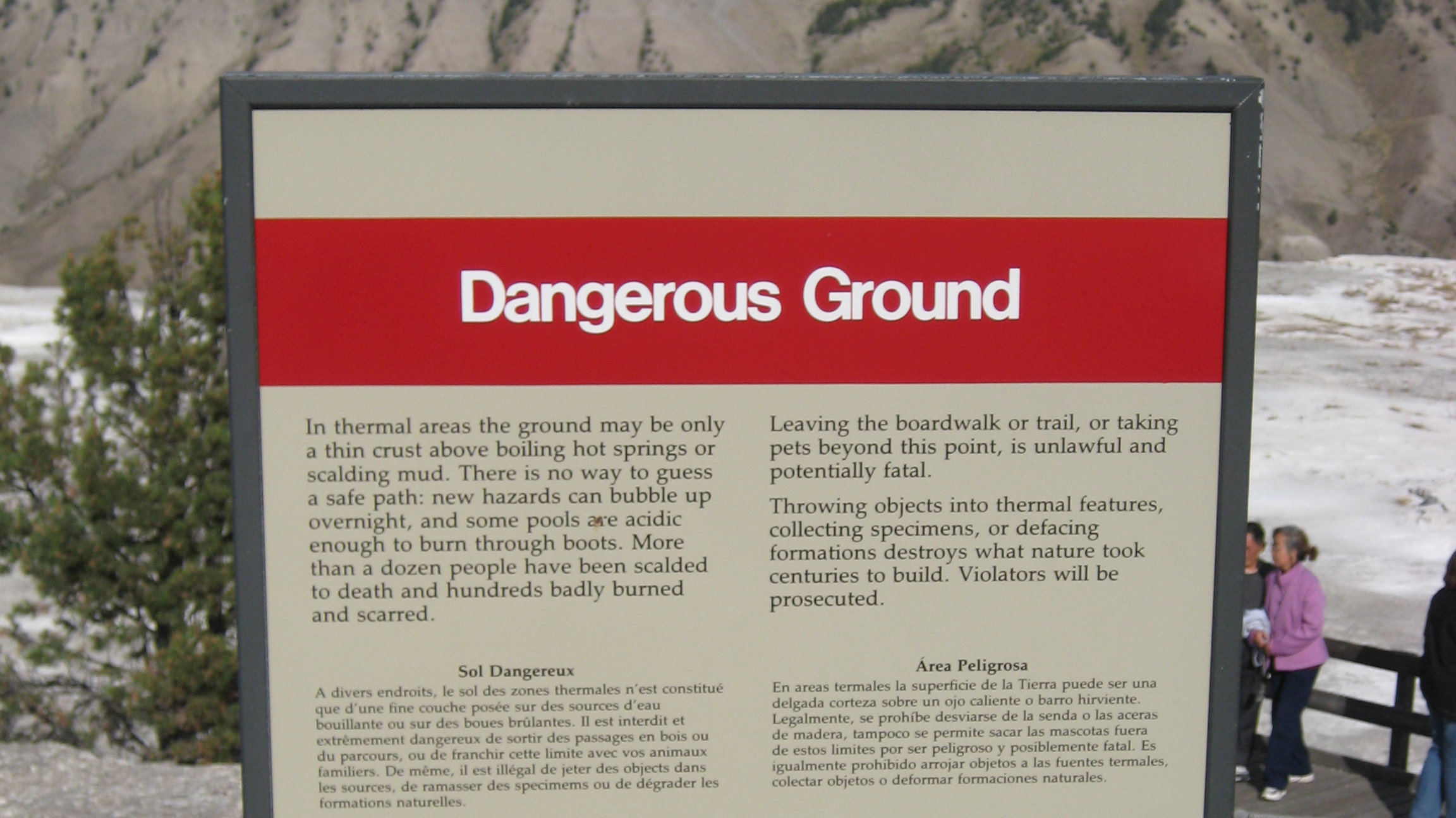

Last week, a 23-year-old Oregon man, Colin Nathaniel Scott, ventured off a boardwalk in Yellowstone National Park and slipped into a boiling, acidic hot spring. He is presumed dead (authorities called off the search for the body due to the danger to rescuers and “the futility of it all”). Yellowstone is America’s and the world’s first national park and remains one of its most famous. A showcase of nature’s grandeur and power, the park rests on a dormant supervolcano that heats hundreds of geysers and springs that draw millions of tourists to the park every year. The boardwalk that Scott left was undoubtedly marked with signs indicating the dangers of venturing out over the thin rock covering the boiling springs. But despite the fact that Scott had served for 20 months as a volunteer at a nature preserve, he nevertheless ignored the warnings and ventured 225 yards from the boardwalk to meet his fate.

A frequent response to these and other rule-violating mishaps that end up in destruction, injury, or death is to invoke stupidity. While difficult to deny, such a response does more to insulate one from tragedy (“I would never do that”) than it does to explain how seemingly normal, reasonably experienced people might ignore the rules and warnings meant to prevent such misfortune. More revealing is the suggestion that the constructed nature of the park—the roads, the boardwalks, the perfect views from the perfect spots—lead to a sense of normalcy and security. The park is, after all, a park: a place people go to relax and enjoy, often with family with young children. The very phrase, “a walk in the park,” connotes safety and ease. Lulled into a sense of security, perhaps some visitors feel that surely if it is so easy to break the rules by walking off the path, it can’t be that dangerous. In light of the resultant accidents, critics remind the public that this is nature, not Disneyland.

Accidents such as these can serve as a lesson, yes, to better respect nature and authority. But the baffling quality of such behavior points to a stranger aspect of parks such as Yellowstone. They are preserved and set aside as pinnacles of nature, primordial being, and “God’s creation” that serve as fonts of inspiration and spiritual rejuvenation. At the same time, they are parks: managed, controlled, comfortable, and relatively easily accessible. The design of the parks encourages the public to concentrate on the former while ignoring the latter. But such concealment of social construction is more of a public secret than an actual deception. Visitors, especially those who venture so brazenly past the warnings of impending death, display an attitude that, for all its reverence and awe in the presence of nature (and surely Scott was drawn by just such appreciation), nevertheless suggests that they feel the parks to be a construction, a fiction, designed to serve their desires and needs. Such an attitude may appear paradoxical, but such paradox grounds the parks as an institution. The parks provide nature in its full glory and reality, but they do so while providing a measure of security and comfort that visitors would not naturally encounter without the institution. Such a paradox is not a logical impossibility, but an operation and a strategy. And as much as that sounds like a game, the stakes can be as real as the ground under foot.

Kerry Mitchell is Director of the Comparative Religion and Culture Program at Global College, Long Island University. He is the author of Spirituality and the State: Managing Nature and Experience in America’s National Parks (NYU Press, 2016).

Kerry Mitchell is Director of the Comparative Religion and Culture Program at Global College, Long Island University. He is the author of Spirituality and the State: Managing Nature and Experience in America’s National Parks (NYU Press, 2016).

Feature Image: “dangerous ground” by sam berlin. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.