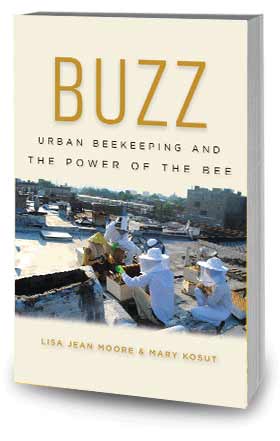

September is National Honey Month! In celebration, we’re featuring the second half of a Q&A with Lisa Jean Moore and Mary Kosut, authors of Buzz: Urban Beekeeping and the Power of the Bee (read the first half here). In part two, Moore and Kosut talk about their experience in the field with bees, the truth about the sting, and bees as the new cause célèbre.

September is National Honey Month! In celebration, we’re featuring the second half of a Q&A with Lisa Jean Moore and Mary Kosut, authors of Buzz: Urban Beekeeping and the Power of the Bee (read the first half here). In part two, Moore and Kosut talk about their experience in the field with bees, the truth about the sting, and bees as the new cause célèbre.

Question: What was it like to be in the field with the bees?

Lisa Jean Moore and Mary Kosut: The first few times with the bees was intense. We weren’t even paying attention to the beekeepers – it was all about being in the space of the bee and moving slowly and deliberately and respecting their airspace. We realized if they just sit on your body and you aren’t freaking out, they won’t sting you. We had to get over all the ways we have been socialized by media messages that bees are bad and could attack at any moment. Bees are actually mostly docile and if you are just smart and contemplative you will be okay. But of course, humans make mistakes.

Beekeeping is also a sensual experience. First is the sound of the bees. The hum can be kind of meditative. It is almost like water in a stream – bees can cause people to really calm down and be in the present. Also, in terms of the embodiment of beekeeping, the hive gives off this extraordinary smell and one of the beekeepers we interviewed, talked about this smell being like truffle oil. She talked about it as being like a “good, heady sex smell” – sort of like the pheromones of sex across species. And we smelled that smell.

When people go and open up the hive, they will sit and watch the bees come and go. These are the intimate embodied relationships people have with the bee.

Q: What about the sting?

LJM and MK: In Buzz, we discuss the sting a lot. There are these affective relationships with bees where fear and anxiety is in involved in the practice. So there is something about the wildness and danger that is attractive to people in New York City in particular. Because beekeeping had been illegal in New York City until a couple years ago because of the fact that they sting, we found beekeepers that actually liked the illegality – it was living on the edge and exciting.

The unpredictability of the bees is also a thrill. There are thousands of them flying in the air and they are making all this noise and it is a little bit intimidating, because they can sting you. People deal with the dangers differently – some beekeepers work without prophylactics. We interviewed this one guy who does beekeeping barefoot. There is a little bit of machoness to it – to quote one of our beekeepers, there’s a “bad-ass-ness” about it. It is kind of a flirtation with wild nature, but not too wild. It is not like keeping a tiger in the city.

Getting stung – being able to say you lived through it and you are going in again – we think that is attractive to people. Because getting stung hurts. The bees die after they get stung, so they actually don’t want to sting you. They do all these warning things to avoid stinging – they release pheromones to signal threat, they change their pitch to show they are angry, they also do this thing called bonking. They fly in and basically hit you on the forehead with their bodies to warn you and make you back off.

Bees die when they sting you because their bottom half falls off. So it is very sacrificial for them – they are sacrificing their life for the security of the hive. The whole is more important than the individual – we as sociologists are very attracted to that idea.

Humans theorize about the bees, comparing the hive to a democracy where all these individuals are working together for the greater good. In Buzz, we discuss how bees are basically this model insect because they are so easily anthropomorphized and a template for how humans are supposed to behave. Historically people have been attracted to bees.

Q: Do killer bees make honey?

LJM and MK: Killer bees are sort of a misnomer – or misnamed. Basically these are bees taken from Africa and studied in South America – mostly Brazil, where they have been studied for certain characteristics. As they are smaller than European honeybees, they reproduce more quickly. But bees are an unpredictable species. They are domesticated, but they don’t always follow what humans want. So some escaped.

They have the capacity to supplant other European hives with their own queen. Once they install their own queen, a hive can turn over to being Africanized. This has been moving up the borders across the U.S.-Mexico border as far north as about Southern Georgia – maybe a bit further. This is tracked by the USDA and other agencies because of the presumed threat of Africanized bees.

They don’t have more venom in their sting – but if they are provoked, they will go farther and longer to sting. The fact that they nest inside buildings and underneath the ground means that humans’ actions sometimes disrupt those bees more than European honeybees because of their nesting patterns. So in Buzz, we talk about that threat of the Africanized bees and how it has been sort of managed through existing tropes of race and racism. Bees have become another way to express anxiety about the border and race and ethnicity. Bees that are out of control are not paying attention to all the rules about entering the country. They are more robust and heartier and that trait is capitalized on and used in a pejorative sense to make us fearful.

Q: What are some of the surprising findings about bees and urban beekeeping?

LJM and MK: One of the things we found so interesting in looking at bees and urban beekeepers and colony collapse disorder (CCD) is that simultaneously, while it is probably a panoply of causes that lead to bees dying, but primarily neonicotinoid – there is also this movement at the same time to save the bees. We liken this to the 1970s save the whales movement.

Bees have become this new mascot or cause célèbre for people to root for or rally behind and this has effects in the urban beekeeping landscape and also for larger corporations like Haagen Dazs or other companies who make saving the bees part of their way of engaging with consumers. It is a pitch to get us concerned by the environment. Bees are seen as so wholesome and so threatened that we need to help them. This is a far cry from when we grew up and were taught to run from bees due to “The Swarm” and other killer bee movies.

In a short time, we have been taught to be concerned about the bees, to worry for them, to want to care for them, to want to buy products that protect them. There is a real shift in how we have seen bees as a real threat to how we seem them now as completely threatened. And this becomes part of our own desire in how to participate to try and help them.