With the 50th anniversary of the1963 March on Washington demonstration in the media’s spotlight, and especially of its heavy emphasis on Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, this light has also shined on the real strategic planners and originators of the actual 1963 March: A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin. Together, Randolph and Rustin made an indefatigable team of seasoned civil rights activists that enabled Dr. King’s now famous speech to be remembered so vividly fifty years later.

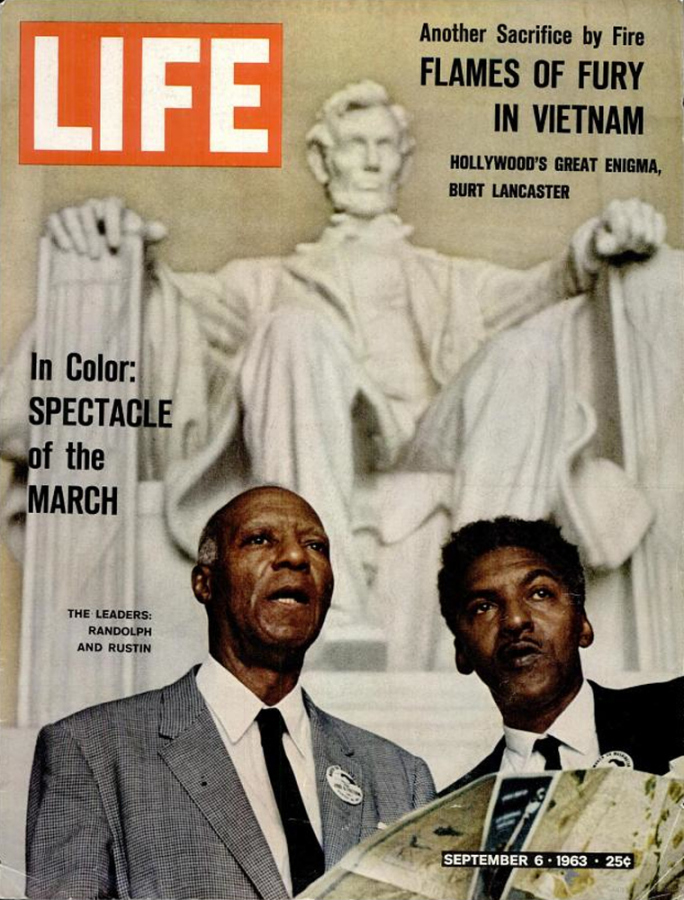

Through the media attention on this anniversary, it has been gratifying to once again see the cover of Life magazine (September 6, 1963) with Randolph and Rustin standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial. At the time of the March, most Americans had viewed these two men as the real stars of the occasion. The 1963 March for Jobs and Freedom was actually the realization of their long-time “dream” to have a dramatic and peaceful demonstration that emphasized the need of all black Americans for economic opportunities and jobs, as well as the more elusive ideal of freedom.

At the time of Randolph’s death in 1979, Rustin described his relationship with Randolph in a variety of ways: father, uncle, adviser, and defender. Yet, Randolph’s and Rustin’s civil rights collaboration got off to a shaky start. As a leader in the youth division of the original March on Washington Movement, Rustin publicly criticized Randolph for calling off the first march scheduled for July 1, 1941. After the war, in 1948, Randolph and Rustin worked together again on a civil disobedience league called the “Committee to End ‘Jim Crow” in the Armed Services.”

When Randolph disbanded the league after President Truman issued Executive Order 9981 which eventually led to the desegregation of the services, Rustin recalled how “a number of ‘Young Turks’ and I decided to outflank Mr. Randolph,” denouncing him in the black press as “an Uncle Tom, a sellout, a reactionary, and an old fogey out of touch with the times.” Afraid that Randolph would not forgive his “treachery,” Rustin avoided Randolph for two years. When Rustin finally mustered the courage to visit Randolph in his New York office, he described the renewal of their friendship in this way:

As I was ushered in, there he was, distinguished and dapper as ever, with arms outstretched, waiting to greet me, the way he had done a decade ago. Motioning me to sit down with that same sweep of his arm, he looked at me, and in a calm, even voice, said: ‘Bayard, where have you been? You know that I have needed you.’

From then on, Randolph and Rustin worked together as the key architects of the modern civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. In 1953, after an incident in Pasadena California when Rustin, an openly gay man, was busted on a morals charge of sexual misconduct, Randolph stood by him and without his friendship, support and considerable influence, Rustin might have been completely ostracized from the civil rights community. Randolph declared “if the fact is, he is homosexual, maybe we need more of them; he’s so talented.”

In 1956, Randolph and Rustin, along with Ella Baker and Stanley Levison, formed an organization called “In Friendship,” a fundraising group committed to providing “economic aid to victims of race terror in the South,” especially for supporters of the Montgomery bus boycott. The group agreed that Rustin, with his extensive experience in nonviolent techniques, could best evaluate the situation in the early days of the boycott. In his brief time there, Rustin worked effectively with the young and inexperienced boycott leader, Martin Luther King. Behind the scenes, Rustin advised Dr. King with his speeches and sat in on many of the boycott’s strategy meetings. Both Randolph and Rustin threw their considerable influence behind King’s emergent leadership of the newest phase of civil rights activity, as Rustin believed “from the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955, for the next two years following to May 1957, [the three year anniversary of the Brown decision] the center of gravity and the center of activity for the whole civil rights movement was the church people and ministers of the south.”

Between 1957 and 1963, this newly formed Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), joined forces with the NAACP, and various labor and working-class groups linked to A. Philip Randolph and other labor leaders to make civil rights history, culminating in the spectacular success of the peaceful August 28, 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

By 1963, A. Philip Randolph was nearing the end of his long years of labor and civil rights activism. In his final tribute to Randolph, Rustin remembered their historic collaboration of that day in the following way:

As the assembly slowly dispersed from the Lincoln Memorial, Rustin saw the tired ‘old gentleman’ standing alone on the podium, looking out on the departing crowds. As Rustin walked up to Randolph, he was surprised to find ‘tears streaming down his cheeks’ the first time he had even seen Randolph show his emotions. Indeed, Randolph was so overcome with the power of that one-day event, in which the black community and the white liberal community came together in their demand for equal treatment under the law, that he ‘could not hold back his feelings.’

How great that the 50th anniversary of the March has brought two forgotten heroes behind the movement, back into public memory.