[This article originally appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle.]

George Zimmerman will not be the last vigilante to stand trial for the killing of an unarmed black teen. While it is convenient to blame the law, such as “make my day” or “stand your ground” laws such as Florida’s, for failing to protect Trayvon Martin and other innocent young black men assumed to be suspicious, the root of this problem lies much deeper in America’s maintenance of all-white neighborhoods.

More than 40 years after the passage of the Fair Housing Act, most housing in America remains segregated along racial lines. Census data from 2010 show that the average white person lives in a neighborhood that is 75 percent white. The average black person lives in a neighborhood that is only 35 percent white.

Income and the size of one’s housing allowance, according to scholars, do not help most blacks escape segregation. Research also shows that minority neighborhoods lack the better schools and other amenities.

The causes of housing segregation are varied. To be sure, some blacks may elect to avoid living in majority white neighborhoods. One reason is violence. Zimmerman is not the first armed individual seeking to protect his neighborhood from someone he deemed an outsider.

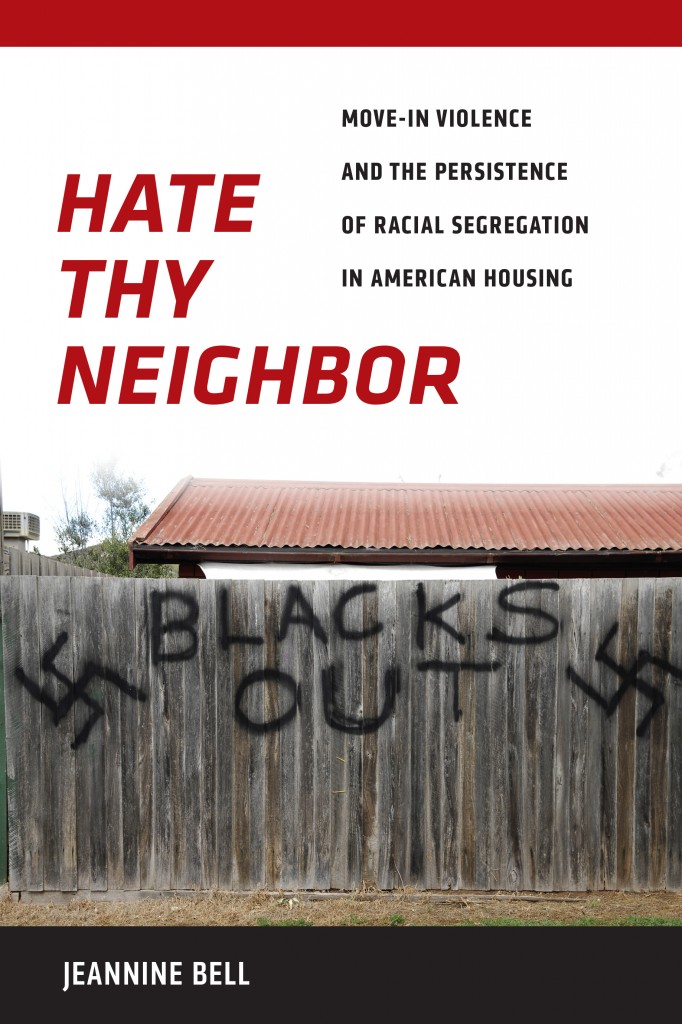

In my research, I have chronicled hundreds of incidents between 1990 and 2010 in which whites targeted minorities who moved into their neighborhood. Cross burning, scrawled slurs and personal assaults- such violence occurs in upscale and working-class neighborhoods alike, in every area of the country, without regard to the wealth or poverty of the minorities moving in.

Blacks living in majority-white neighborhoods also face problems when inviting friends or relatives to visit. Martin’s killing highlights the vulnerability of these guests to white stereotyping that sees these black visitors, who dare to cross the color line, as potential criminals.

It is not disputed that Zimmerman initiated the encounter with Martin when he deemed the young man suspicious. It was only Martin’s blackness, not his size, nor his age, nor his behavior that sparked Zimmerman’s initial concern. Zimmerman argued that he feared for his life when his supposed assailant was an unarmed teenager he outweighed by more than 100 pounds.

Too many Americans are harmed by what I have termed the “integration nightmare.” They assume that “good” and “safe” neighborhoods are neighborhoods without black people in them. Thus, they see the arrival of black neighbors as disruptive; they see more diversity as threatening.

Ironically, the initial disruption to these white residents is psychological – the fear that more blacks will follow and that their guests will be criminals. When violence follows, it is usually initiated by whites acting out their irrational fears.

Nothing can bring back Martin, but as a society perhaps we can learn from the circumstances of his death. To prevent killings and other violence, we need to think differently; in particular, we need to recognize the value of racial and ethnic diversity in America’s neighborhoods.

Our strength as a nation lies in our learning from one another and building upon our common humanity. There is no better way to reduce the polarizing violence and politics than building integrated social networks based on living in proximity to one another.

Segregation needs to finally die and the integration nightmare is just that, a bad dream with little basis in reality.

Jeannine Bell is a professor at Indiana University Maurer School of Law and author of Hate Thy Neighbor: Racial Violence and the Persistence of Segregation in American Housing (NYU Press, 2013).