—Daniel Katz

Get the e-book of All Together Different on Amazon now for only $0.99.

This year the Supreme Court threw a kidney punch to organized labor by deciding in favor of Mark Janus, an Illinois State worker represented by the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees. Janus, who refused to join a union, objected to his legal obligation to pay dues to the union. Overnight, hundreds of local and state unions throughout the US lost the ability to collect dues from non-members for the services they provide, such as organizing, representing employees in disciplinary hearings, negotiating benefits, and lobbying. The decision was only the most recent and broadest attack on working and poor people in a torrent of assaults designed, funded, and executed by billionaires like the Koch brothers. Working families continued to suffer as the housing and student debt crises deepened this year, helped along by Trump administration policies to eliminate modest regulations enacted by President Obama. Trump continued Obama’s program to deport massive numbers of undocumented workers and their families. And Trump has opened the door of the White House to white supremacists and other alt-right bigots who support the disenfranchisement of poor, black, and brown people. Meanwhile, union membership numbers declined along with their power to keep even many unionized workers out of poverty.

Yet, countervailing social forces suggest that working people and their allies have good reasons to cheer as well. Teachers in West Virginia, who ignored laws that prohibited them from collective bargaining, erupted as a force for working-class militancy—risking their livelihoods and personal liberties as they went on an illegal strike for nine days, forcing the state to meet their demands. Their labor siblings in several red states followed suit by striking or threatening to strike—winning increasingly larger concessions from their public employers, including pay raises, better health insurance, and increased funding for school budgets. At the same time, Bernie Sanders leveraged his remarkable race against Hillary Clinton for the democratic nomination in 2016 to a build a grass roots movement of politicians who are winning primaries this year as proud pro-labor and anti-capitalist democratic socialists.

Are these brief and isolated instances, or a harbinger of something more powerful and lasting?

To inform our perspective, we can look back to periods in American history when the most unlikely workers in the most unlikely places risked life, limb, livelihood, and liberty to build unions and fight back against the most powerful forces of Capital. During World War I, unions made unprecedented gains topping five million members. After the war, less than two years after the Russian Revolution, workers in scores of industries struck across the US, from Boston police officers to thousands of immigrant, unskilled, steel workers in states like Pennsylvania and Colorado. Fearing a homegrown revolutionary moment, government officials, manufacturers, and popular media conspired to crush radicalism and beat back union organizing. The Red Scare (1919) resulted in closing offices of union and ethnic publications, jailing accused subversives, and deporting thousands of foreigners. Mine owners hired private armies and controlled local police forces that engaged in pitched-gun battles with striking miners. In West Virginia, one sheriff went to the extreme of dropping bombs from airplanes during the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain. Manufacturers in many industries devised the American Plan to spy on union meetings and intimidate and blacklist union activists. The Ku Klux Klan re-emerged in the 1920s, terrorizing blacks who dared to move off the plantations and into southern cities or out of the south altogether.

Still, during the 1920s, working people refused to give up. Communist and Socialist organizers continued to build unions among immigrant and women workers in the garment industries of New York City and Chicago. Thousands of workers struck the Gastonia, North Carolina and Elizabethton, Tennessee textile mills in 1929. The United Mine Workers of America, in decline throughout the decade, continued to organize and strike. The American Federation of Labor created the Brookwood Labor College, where organizers from the miners, garment, and textile unions met in the mid-1920s to collaborate on models for developing industrial unions within the mainstream labor movement. Black men and women formed the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1925, the same year thousands of Klansmen marched in Washington, D.C. And in 1926, under labor pressure that threatened to cripple the American economy, Congress passed and President Calvin Coolidge signed the Railway Labor Act, mandating collective bargaining for railway workers.

By the beginning of the 1930s, labor had lost 40% of its 1918 membership, and working people bore the brunt of the deepest and most prolonged depression in American history. But the persistence of unions, radical political parties, and ordinary people throughout the 1920s built the momentum needed to demand the protections of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s. Working families engaged in general strikes in 1934, shutting down cities from Toledo to San Francisco, prompting the Wagner Act in 1935 that granted workers in basic industry the right to form unions and bargain collectively. That same year, the unions formed the Committee (later Congress) of Industrial Organizations that spurred labor growth for a generation. In a few short years, millions of workers won social security benefits for the first time, along with minimum wages and maximum hours. By the end of World War II, in less than a decade, the ranks of organized labor multiplied by a factor of four, and millions of working families climbed out of poverty.

These lessons of our American working past give today’s working people hope that even under the most extreme circumstances—like being bullied by their government—workers have found their footing, fought back, and won. The American labor movement was hobbled by the Janus decision this year. To what degree, we do not yet know. But this year’s militancy among teachers reminds us that such injuries can heal, and workers’ movements can regroup to become stronger than ever.

Daniel Katz is the Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at Alfred State College. A former union organizer, he is a member of the Board of Directors of Jews for Racial and Economic Justice in New York City. He is the author of All Together Different: Yiddish Socialists, Garment Workers, and the Labor Roots of Multiculturalism (2013).

Daniel Katz is the Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at Alfred State College. A former union organizer, he is a member of the Board of Directors of Jews for Racial and Economic Justice in New York City. He is the author of All Together Different: Yiddish Socialists, Garment Workers, and the Labor Roots of Multiculturalism (2013).

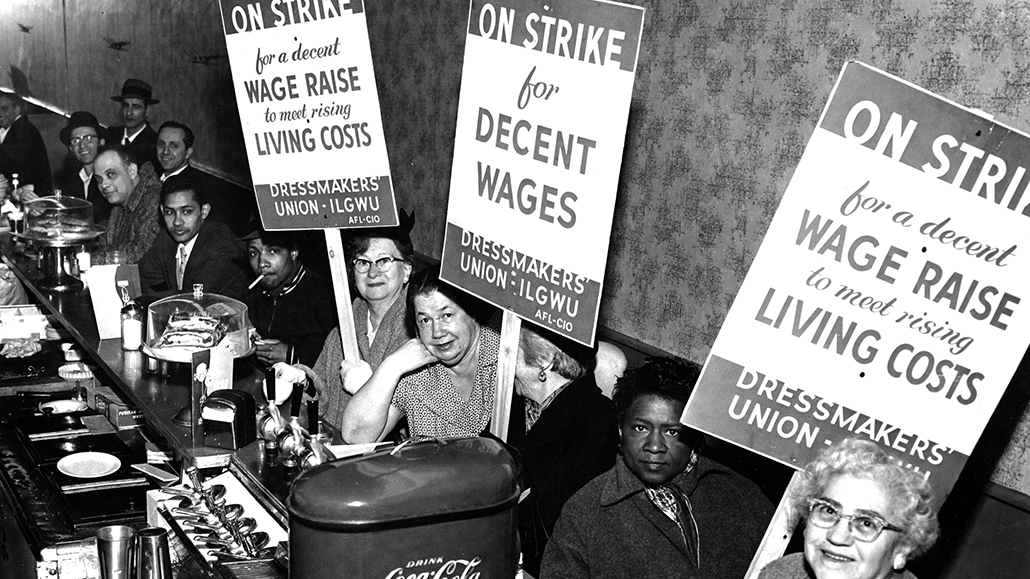

Feature image: “Striking dressmakers take a break in a diner.” CC by 2.0 from The Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives.