—Kidada E. Williams

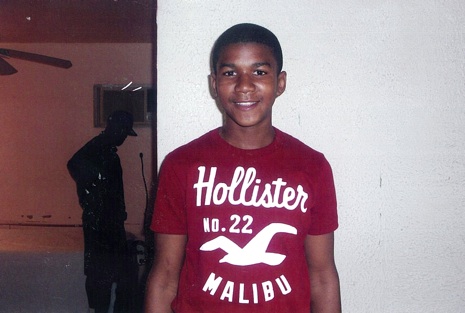

Many Americans cannot understand why so many African Americans and their allies have rallied around the family of Trayvon Martin, the 17-year-old killed by a white Hispanic neighborhood watch volunteer, George Zimmerman, who claimed self-defense under Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” law. People in Central Florida and beyond pushed so hard to see Zimmerman arrested that Sanford, Florida, authorities convened a grand jury investigation and the Department of Justice launched a probe into the killing. This mobilization sprouted from an shared understanding that Martin’s death and the acceptance of Zimmerman’s claims of self-defense are not isolated; they are tied to the long history and legacy of extralegal racial violence directed at African Americans, dating back to the days of slavery.

Extralegal violence typically involves the decision to step outside the boundaries of the legal system to violently exact justice while purporting to be operating in conjunction with the legal system and thereby exempt from prosecution. The racialization of extralegal violence, directed at African American men, women, and children, can be traced to the history of southern slavery. Members of the slaveholding class enjoyed full control over the discipline and punishment of the black people they enslaved. Authorities reasoned that white men with property, especially human property, should maintain the right to assert authority over legal and judicial matters not only on their land but also in their communities. Once slavery ended, many members of the ex-slaveholding class argued that they should retain what they saw as their republican rights to extralegal violence against black people. They argued that this was the only way to protect the lives and political and economic interests of white southerners against a “black criminality” unchecked by slavery. Southern whites attacked not only black people who broke laws; they also attacked black people who transgressed white people’s racial authority by resisting sexual or economic exploitation, voting in elections, crossing the color-line, demanding a warrant for an arrest, and defending themselves against violence. Although such authority was bestowed upon slaveholders, the segregationist culture established in the 1880s and 1890s led even non-slaveholding whites and European immigrants to become invested in using extralegal violence to subjugate black people. This resulted in the creation of a culture in which the use of extralegal violence against black people, including lynching, was tolerated and in some cases promoted.

African Americans understood the hazards of the new racial order. Black families socialized their children, especially their males, on how to interact with and behave around white people, as a way of avoiding violent attacks from white people who would not be punished. It took the racial progress that African Americans and their allies achieved through the civil rights struggle to change many white Americans’ tolerance of extralegal racial violence and their willingness to let the criminal justice system handle the administration of justice. The historical imprint of this extralegal violence as a way to regulate black people, however, remained—and with it, the calcification of many black people’s fear and distrust of unfamiliar white people. W. E. B. Du Bois captured this in “The Souls of White Folk,” when he explained that the rise of racial disfranchisement, segregation, and violence in the late 19th-century forced him to look anew at white people. “Of them I am singularly clairvoyant,” he wrote. “I see and through them. I see them from unusual points of vantage…I see their souls undressed and from the back and side.” African Americans had to carry themselves in a particular way, to see in and through white people, and to view them from unusual points of vantage to try to figure out their intentions and whether they might harm or kill them. Honest conversations with and amongst African Americans reveal that many of them still try to see the souls of any strange white folk they encounter.

The outrage that some Americans feel about Trayvon Martin’s killing is shaped by their knowledge of this history, its legacy of fear and distrust, and what they believe is its role in guiding authorities’ decisions to take George Zimmerman at his word, that he killed Martin in self-defense. On its surface, Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” law is race-neutral but African Americans and their allies know that its application cannot be separated from the history of extralegal racial violence. Reports on the case, including the 911 calls, do not suggest that Martin was engaging in any criminal behavior; he was walking home from the local 7-Eleven. George Zimmerman thought Martin was “suspicious,” he confronted him, shot and killed him, and then claimed self-defense. Authorities accepted Zimmerman at his word and failed to consider the larger context of his behavior which included a history of aggressive vigilantism before the event, his decision to break the basic rules for neighborhood watch volunteers, and his disregard of the 911 dispatcher’s recommendation that he stay in his car. With the grand jury and DOJ investigations underway, the final chapter of this case remains unwritten. One critical chapter in the histories written on this case will be African Americans’ and their allies’ decisions to mobilize to try to make law enforcement and the nation understand many Americans’ opposition to this violence and their willingness to use their collective might to try to right the wrongs of the past by bringing justice to this and other grieving families.

Kidada E. Williams is the author of They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I.