—Michael D. White and Henry F. Fradella

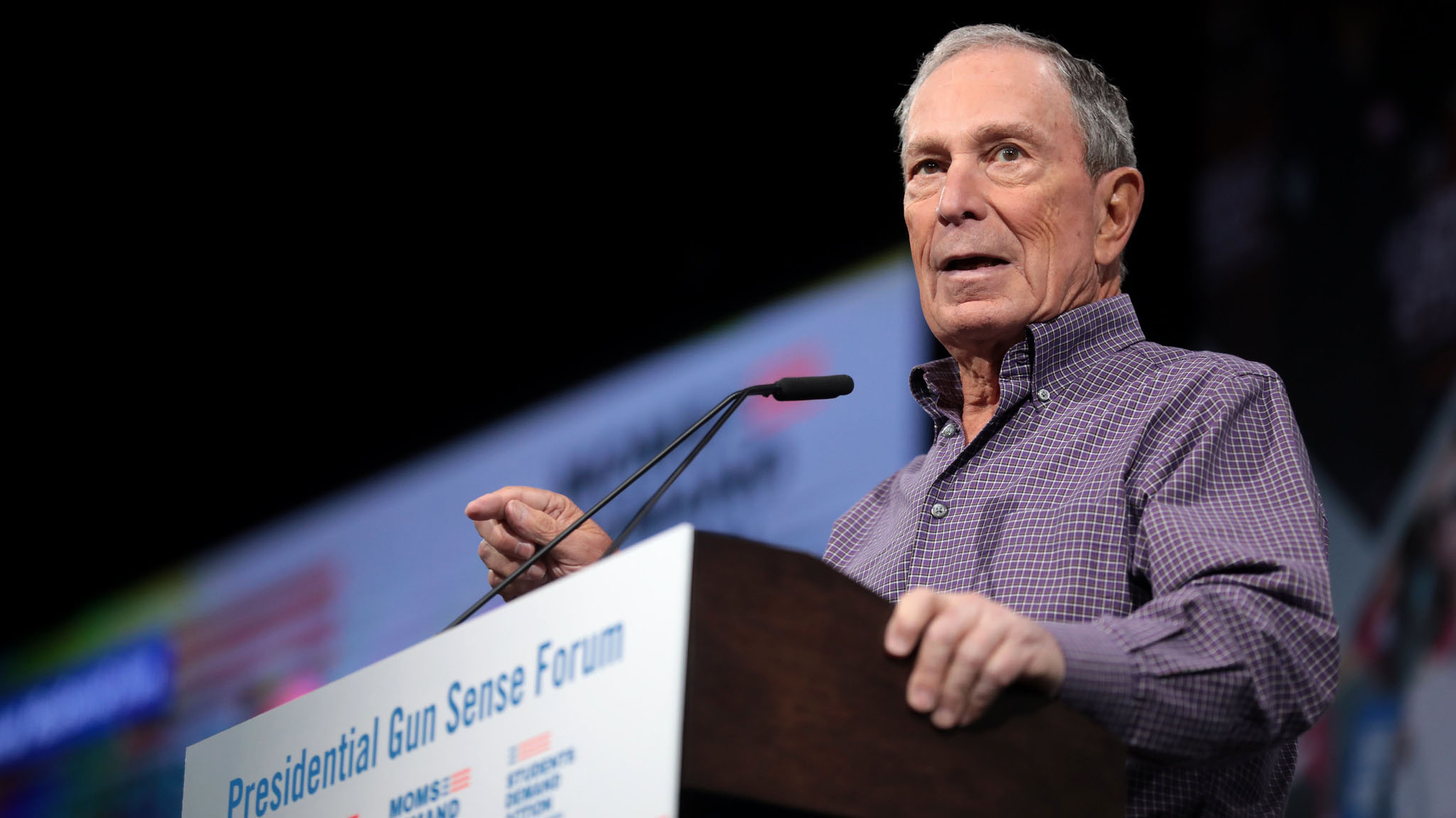

As he gears up for a potential run for the U.S. presidency, former NYC Mayor Michael Bloomberg reversed his long-standing support of that city’s aggressive “Stop, Question, and Frisk” (SQF) strategy. Bloomberg had been one of SQF’s most vocal proponents, boasting it had “saved countless lives” even after a federal judge had declared the NYPD program unconstitutional. Last Sunday, however, while speaking at a predominately Black church in Brooklyn, Bloomberg said he was sorry for SQF, adding, “I can’t change history. However today, I want you to know that I realize back then I was wrong.” But for what exactly was he apologizing?

Although SQF predated Bloomberg’s election as mayor, the program ratcheted-up under his leadership far beyond its constitutionally sanctioned contours. Stop-and-frisk has a long history as a policing tactic rooted in particularized, reasonable suspicion that a specific individual is involved in criminal activity. However, in NYC and several other U.S. jurisdictions, this tactic morphed into a widespread, aggressive crime-control strategy. With Bloomberg’s unwavering support, NYPD officers routinely stopped, questioned, and often patted-down hundreds of thousands of people each year—roughly 87% of whom were Black or Hispanic—to see if they were carrying weapons or drugs. The NYPD argued that they applied SQF only when officers had reasonable suspicion that someone was breaking the law, but given their low “hit rates,” such claims seem quite implausible. Only 6% of all stops resulted in an arrest and less than 1% resulted in the seizure of a firearm; by contrast, 88% of all stops yielded no evidence of any criminal wrongdoing. Was Bloomberg apologizing for the aggressive use of SQF without particularized suspicion which violated New Yorker’s Fourth Amendment rights against unreasonable searches and seizures?

SQF, along with other philosophical, structural, and operational changes to the NYPD, coincided with historic drops in crime, especially homicides. Given the apparent association between the crime drop and the SQF program, the NYPD steadily increased its use of the tactic into the 2000s. Bloomberg credited the precipitous decrease in crime to SQF: “Every day, Commissioner Kelly and I wake up determined to keep New Yorkers safe and save lives. And our crime strategies and tools, including stop, question, frisk, have made New York City the safest big city in America.” But it is not possible to disentangle SQF from a number of other programs that were simultaneously implemented. Moreover, if SQF had been the driving force in reducing crime, crime rates should have increased when SQF was discontinued. But that did not occur. From 2011 to 2017, the number of stops conducted by NYPD officers declined by approximately 98%. Yet, in 2018, NYC marked the lowest number of index crimes—robberies, burglaries, motor vehicle larcenies, and murders—in nearly 70 years. Still, as recently as January of 2019, Bloomberg pushed the dubious claim that SQF had been responsible for the drop in homicides during his tenure as mayor. Did his recent apology encompass remorse for perpetuating a false narrative about policing and crime?

During his apology, Bloomberg acknowledged the disproportionate impact SQF had on people and communities of color. “Our focus was on saving lives. The fact is, far too many innocent people were being stopped while we tried to do that. And the overwhelming majority of them were Black and Latino.” He went on to say that while he was in office, he did not understand the full impact SQF had on people of color. But it is unclear if Bloomberg really comprehends or cares about the extent to which racial profiling was part-and-parcel of SQF. Indeed, when a federal judge declared that SQF’s targeting of racial and ethnic minorities violated New Yorker’s Fourteenth Amendment rights to equal protection of law, Bloomberg sharply criticized the ruling and even disparaged the judge’s understanding of constitutional law. Bloomberg did not apologize to this judge, so perhaps he was apologizing for violating the civil rights of all the innocent people of color who were detained during the SQF program?

Widespread use of SQF as a crime control strategy not only led to violations of citizens’ constitutional rights, but also strained police-community relationships, damaged police legitimacy, and generated significant emotional, psychological, and physical consequences to citizens, especially those of racial or ethnic minority backgrounds. Is Bloomberg sorry for that, too? And if so, is an apology enough? The inadequacies of Bloomberg’s nebulous apology notwithstanding, we believe that stop-and-frisk has an important place in contemporary policing, provided that it is employed within the constitutional framework of being a particularized tactic rather than a widespread crime control strategy. Individual police officers should stop and question people when objective circumstances—not someone’s race or ethnicity—give rise to reasonable suspicion of criminal activity. Proper mechanisms must be in place to control the exercise of officer discretion in this context, including a careful selection process during recruitment, an empirically supported training regimen, properly supported administrative policies, objective supervision protocols to increase accountability and transparency, and external oversight.

Technology also offers a fruitful avenue in order to better control officer decision-making. Body-worn cameras (BWCs), for example, offer an opportunity for police departments to track, monitor, and control officer decision making during stop-and-frisk activities through systematic review of officers’ BWC footage by supervisors, training units, internal affairs units, or external auditors. BWCs also represent an opportunity for police departments to demonstrate accountability and transparency to their communities.

If used properly, stop-and-frisk can also be successfully applied within several contemporary policing frameworks, including community- and problem-oriented policing, hot spot policing, and targeted offender policing. An advantage to these frameworks is that they allow police to focus on procedural justice elements in order to enhance their legitimacy among their respective communities. This approach emphasizes officers treating people with dignity and respect; giving individuals “voice” during encounters (an opportunity to tell their side of the story); being neutral and transparent in decision making; and conveying trustworthy motives. Together, these approaches can better enhance police legitimacy, promote constitutional standards, and ensure officer safety, while allowing officers to retain their effective crime fighter status.

For more on our thoughts regarding stop-and-frisk, check out our book, Stop and Frisk: The Use and Abuse of a Controversial Policing Tactic, winner of the 2019 Outstanding Book Award from the American Society of Criminology’s Division of Policing.

Michael D. White is Professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Arizona State University and the Associate Director of ASU’s Center for Violence Prevention and Community Safety. His publications include Jammed Up: Bad Cops, Police Misconduct, and the New York City Police Department. Henry F. Fradella is Professor and Associate Director in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Arizona State University. His publications include America’s Courts and the Criminal Justice System. They are the co-authors of Stop and Frisk: The Use and Abuse of a Controversial Policing Tactic, available from NYU Press.

Michael D. White is Professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Arizona State University and the Associate Director of ASU’s Center for Violence Prevention and Community Safety. His publications include Jammed Up: Bad Cops, Police Misconduct, and the New York City Police Department. Henry F. Fradella is Professor and Associate Director in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Arizona State University. His publications include America’s Courts and the Criminal Justice System. They are the co-authors of Stop and Frisk: The Use and Abuse of a Controversial Policing Tactic, available from NYU Press.

Feature image by Gage Skidmore on Flickr