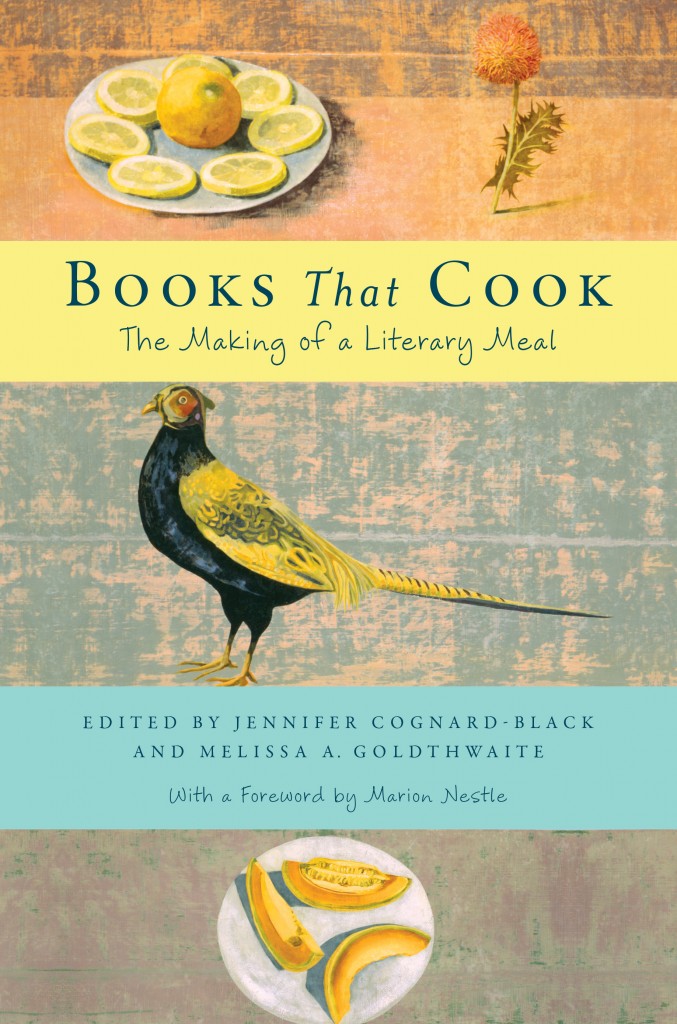

During the month of September, we’re celebrating the publication of our first literary cookbook, Books That Cook: The Making of a Literary Meal by rounding up some of our bravest “chefs” at the Press to take on the task of cooking this book! In the next few weeks, we’ll be serving up reviews, odes, and confessions from Press staff members who attempted various recipes à la minute.

During the month of September, we’re celebrating the publication of our first literary cookbook, Books That Cook: The Making of a Literary Meal by rounding up some of our bravest “chefs” at the Press to take on the task of cooking this book! In the next few weeks, we’ll be serving up reviews, odes, and confessions from Press staff members who attempted various recipes à la minute.

Read, savor, and be sure to enter our giveaway for a chance to win a copy of the book before it ends on September 21!

Up next on the menu: Managing Editor Dorothea Stillman Halliday masters the art of l’artichaut.

My father would have loved Books That Cook, uniting as it does two of his greatest passions: books and food. My father read voraciously, books of all kinds, several at one time, and among those were cookbooks and literary food writing. He read about the history of foods and cuisines and the culinary practices of different cultures. He traveled widely and loved to taste the world. But every night at home he sat down to a disappointing dinner.

My parents lived in Europe during their early married life and then again later, after my siblings and I were part of the mix. My father’s tastes were full of herbs and spices to begin with and grew only more sophisticated after living abroad, while my mother seemed incapable of distinguishing between delicious and dreadful food. Her culinary ability and discernment were in the great American (pre–Julia Child) tradition of the blandest meat and most overcooked vegetables, puddles of mayonnaise, and a cabinet full of prefab foods. Why make fresh potatoes, when you could make potato flakes from a box just by adding them to hot water? Why even drink fresh milk when you could mix milk from a powder? The nutrition was what mattered to her, and that was all.

Unfortunately for my parents, who were newlyweds in the late forties, they were imprisoned in the gender roles of their time. My father went into the world and worked; my mother stayed home and cooked. He read Mastering the Art of French Cooking and watched Julia Child on TV, but he felt constrained to do no more food preparation than to put cream cheese and lox on a bagel. The wife did the cooking. The husband’s lot was to sit and be served—poor wretch. He dreamed of gastronomy; she dreamed of getting all our nutrients via vitamin pills. Needless to say, this caused considerable marital friction, and were it not for frequent dinners at the local Chinese restaurant, things might have gotten really ugly.

By the mid-seventies, the culture and my parents had both evolved enough that my father finally declared that he would do the cooking from now on. The dinner table became a happier place. And the food was much improved too. My mother was relieved to be liberated from the pressure of preparing meals that continually fell short of expectations. But she never understood what the big deal was. She always greeted any culinary preparation by expounding the nutritional value of the components: “Oh, carrots are very good for you. They’re full of vitamin A” and “Spinach is loaded with iron.”

If you’ve ever painstakingly prepared a delicious meal for someone and been greeted by this kind of response, then you know that the friction at the dinner table did not disappear altogether. My father would sigh in exasperation with her lack of appreciation but would console himself with the responses he got from the rest of us and with his own enjoyment of his meal. Once, while serving up one of his creations, he loaded up a fork and offered it to my mother. “Try this,” he said. “It’s got something in it that’s very good for you: flavor.”

When asked to select a recipe from Books That Cook to write about, I chose artichokes with beurre au citron, lemon butter sauce. The dish is both simple and fine, and it is one of a very few I remember my mother making that we all truly enjoyed. I don’t know if she learned from Julia Child’s recipe or from somewhere else, but even my mother could boil an artichoke and squeeze lemon juice into melted butter.

I remember how exotic it seemed to eat a huge flower bud. It was a gustatory adventure, even a quest: We sought the hidden treasure, the succulent heart. We peeled the petals away one at a time, avoiding the sharp points—my mother either didn’t know, or didn’t bother, to cut them off. We dipped the petals in the lemon butter and scraped the “meat” off with our teeth. We worked our way past the soft inner leaves of pale green and purple, down to the choke, which guarded the heart. Once past its defenses, we beheld the grail. And there was peace and harmony at the table.

The artichoke was good, even in the hands of an unskilled cook. And it still is.

Dorothea Stillman Halliday is Managing Editor at NYU Press.