—Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic

Hate speech entered into U.S. policy and legal discourse in the mid-1980s when a number of critical race scholars urged that hate speech be considered a tort—a civil action in which a victimized person, usually a minority, sued another for damages inflected via racial insults or invective in a one-on-one situation. One of us (Delgado) pointed out that a number of courts were already doing so under the rubric of well-established torts such as assault, battery, defamation, or intentional infliction of emotional distress.

European legislators had addressed hate speech in the form of national laws criminalizing it even earlier, with the example of Hitler’s Holocaust fresh in their minds, and at least one legal scholar (Mari Matsuda, Hawaii) urged that their U.S. counterparts do so as well.

With the advent of affirmative action, American campuses’ populations became much more diverse. As racial tensions grew, hate speech again became a front-burner issue as many colleges and universities enacted campus speech codes aimed at curbing the most disruptive forms of racial vituperation. Around the same time, workplace law began recognizing the harm of a racially hostile workplace and allowing workers to sue their employers for tolerating work environments rife with racial paraphernalia, such as swastikas or nooses, and epithets, slurs, and invective.

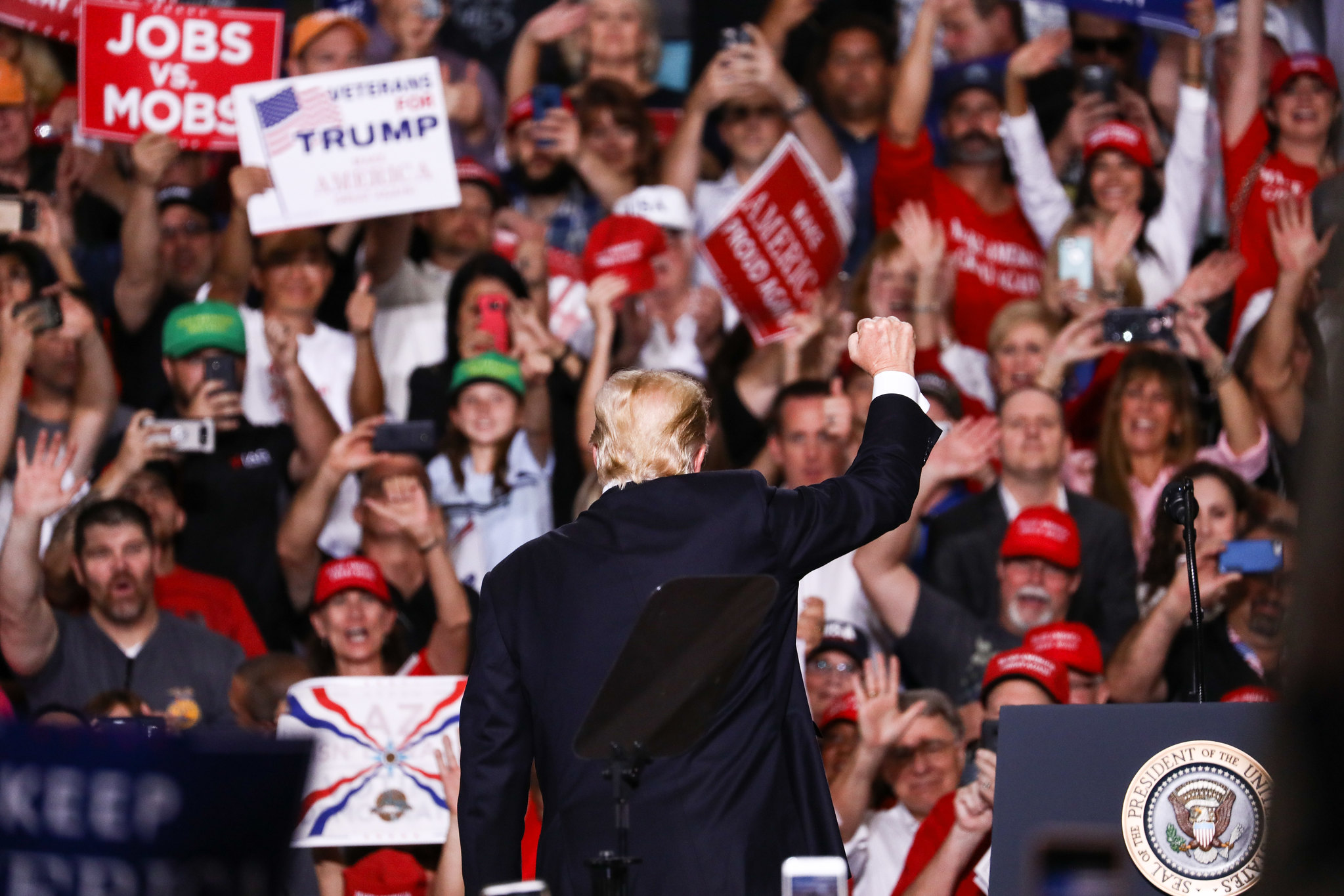

With the election of President Donald Trump, a new form of hate speech has emerged in the form of vitriolic tweets, rallies, and speeches lambasting Mexicans, Muslims, and African Americans. Scholars, journalists, and ordinary citizens are wondering: What can stop a President whose popularity with a segment of the electorate—his “base”—seems a function of how hatefully he can speak about minorities, immigrants, and foreigners.

Three avenues seem possible. Those repulsed by his deeds and speech can organize to vote him and his party out of office at the next election. Congress may also vote to impeach him if they deem his behavior to rise to the level of high crimes or misdemeanors. Finally, victims of white extremist violence may sue the president or his spokesmen for physical injuries or deaths suffered at the hands of crowds or lone wolf attackers who appear to have found inspiration in his words and action, perhaps naming the President or his administration as inciters or co-conspirators.

Federal courts are unlikely to accept jurisdiction of such suits, but state courts may prove receptive to a well-argued complaint, just as they have in the form of tort actions for “words that wound.” Congress and state legislatures may make such suits actionable by enacting legislation expressly aimed at curbing Executive speech of a hateful nature. If workplace supervisors and corporate executives can be held accountable for fomenting or tolerating a racist work climate, it would seem no less feasible to put political leaders—chief Executives—on notice that they are responsible as well.

Derogatory statements by the President seem to have lain behind the behavior of a number of recent mass shooters. The question these atrocities raise is whether a President’s right of free speech ends at a child’s non-bulletproof vest.

Richard Delgado is John J. Sparkman Chair of Law at the University of Alabama and one of the founders of critical race theory. His books include The Rodrigo Chronicles (NYU Press). Jean Stefancic is Professor and Clement Research Affiliate at the University of Alabama School of Law. Her books include No Mercy: How Conservative Think Tanks and Foundations Changed America’s Social Agenda and How Lawyers Lose Their Way: A Profession Fails Its Creative Minds. Together they are the editors of The Latino/a Condition: A Critical Reader and the authors of Must We Defend Nazis?: Hate Speech, Pornography, and the New First Amendment, both available from NYU Press.

Richard Delgado is John J. Sparkman Chair of Law at the University of Alabama and one of the founders of critical race theory. His books include The Rodrigo Chronicles (NYU Press). Jean Stefancic is Professor and Clement Research Affiliate at the University of Alabama School of Law. Her books include No Mercy: How Conservative Think Tanks and Foundations Changed America’s Social Agenda and How Lawyers Lose Their Way: A Profession Fails Its Creative Minds. Together they are the editors of The Latino/a Condition: A Critical Reader and the authors of Must We Defend Nazis?: Hate Speech, Pornography, and the New First Amendment, both available from NYU Press.

Featured image of Trump MAGA rally in Mesa, Arizona from Charlotte Cuthbertson/The Epoch Times, used under CC 2.0.