—Marieke Liem and Jan Banning

“I just felt isolated, like, you know, I felt as if I was placed in a foreign country, I didn’t know anybody, nobody knew me, I didn’t know my position, my role. You know, there was no structure, there was nothing, it was just like, it was like being tossed, it is hard for me to describe, but it is just like being tossed in some plains where you have no survival skills, no tools, no nothing.”

Ruben was incarcerated for fifteen years before being granted parole. His story is not unique. Today, one out of every nine prisoners is serving a life sentence. This adds up to roughly 160,000 people, or an entire midsize U.S. city, such as Eugene, Oregon, or Fort Collins, Colorado. Even though a proportion is serving a sentence of life without parole, the majority of lifers will at one point, most often after 30 years or more, be paroled to society.

It is to be expected that in the following months, there will be many more cases such as Ruben’s, now that President Obama picks up the pace of commuting prison sentences for federal drug offenders, including life sentences. In a recent Washington Times article, White House counsel Neil Eggleston said more grants of clemency are coming. Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, said the president could conceivably commute the sentences of a total of 1,000 to 1,500 federal inmates by the time he leaves office in January.

For two-plus years, Marieke interviewed over sixty lifers like Ruben, who had been incarcerated for decades. After release, some were successful in staying outside the prison walls, while others found themselves back behind bars. She became intrigued by the questions: What happens after decades of confinement, including prolonged periods in solitary confinement? How do they fare after their release?

To answer this question, she talked to men and women who had committed a homicide, had served a life sentence for this crime, and were released or paroled following their sentence. In her book After Life Imprisonment, she explores the lives of these men and women before, during, and after serving a life sentence.

There are several ways in which prison can influence people’s lives post-release: first, as a deterrent for future criminal behavior, second, as a breeding ground for future crime, or third, simply as a “deep freeze,” which implies that offenders come out the exact same way they came in. In her book, she found much support for a fourth perspective: namely, that prison itself creates a unique set of mental and social problems that inhibits the offender upon his or her return. Long-term imprisonment appears to be associated with a high degree of institutionalization, or prisonization. This implies that the prison environment socializes inmates by socially segregating them from society.

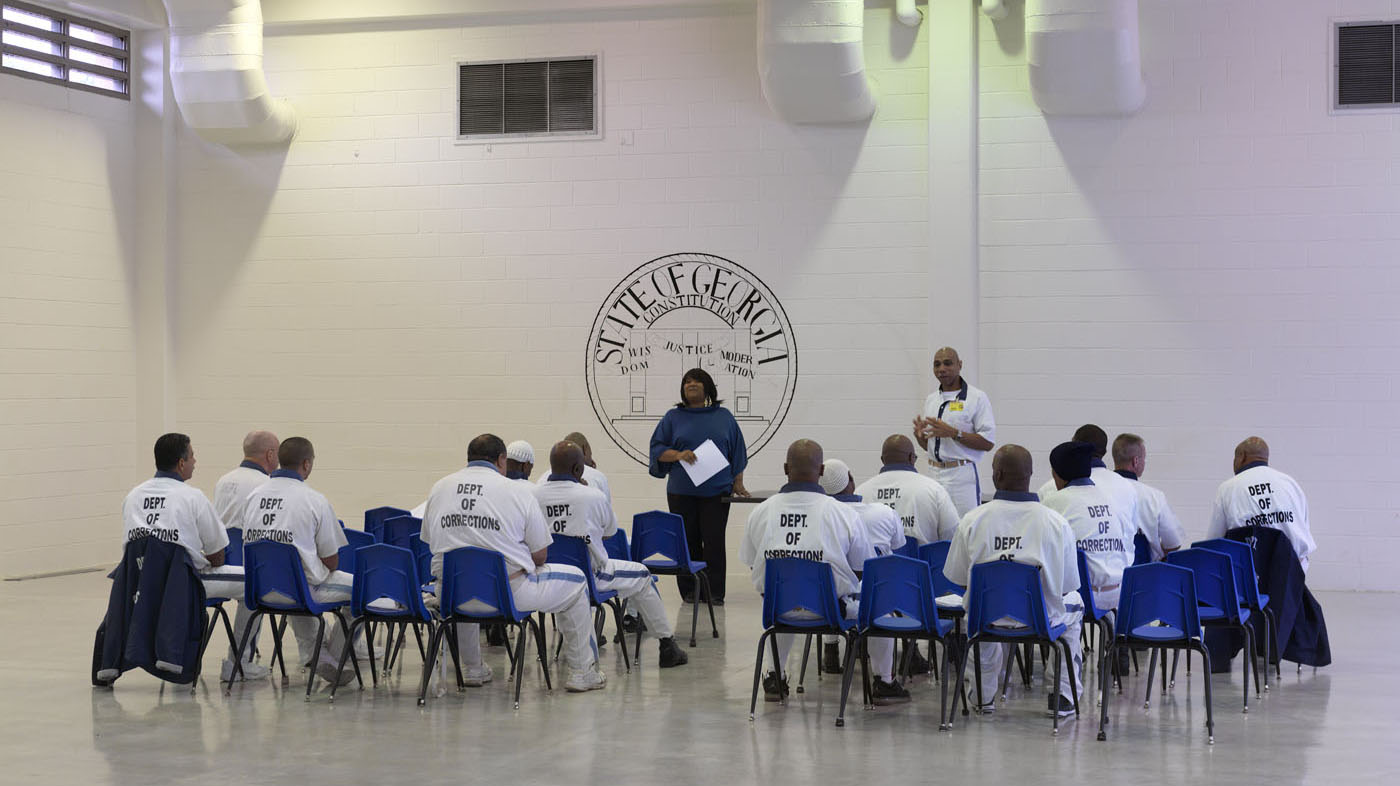

Jan Banning, whose new book, Law & Order, was published around the same time as After Life Imprisonment, illustrates such profound segregation from society in an impressive series of photographs of police, courts, jails, and prisons, including US prisons. While making international comparisons between the US, Colombia, Uganda and France, Banning paraphrases Dostoyevsky:

“Show me your prisons, and I’ll show you the state of your civilization. Can we be proud of what we see?”

[slideshow_deploy id=’8813′]

All images are from Law & Order: The World of Criminal Justice and were used with permission from the author Jan Banning.

Without making judgments, these photos force us to address questions such as: Is prison the best deterrent for crime? And if so, what is it we want to achieve? Isolate people so as to protect society? Deterrence? Retaliation? Or correction? Let us think critically about these fundamental questions, delve into the facts and consider the (unwanted) by-products of spending time behind bars, particularly for those who serve decades.

Over time, as family and friends move on or pass away, lifers are decreasingly exposed to pro-social influences. The longer the time in custody, the less likely it is for prisoners to find a job, re-establish ties with others, and stay out of trouble. Interviews with lifers showed that without any job experience and the stigma of being not only an ex-prisoner, but also a lifer, the prospects of obtaining work were meager at best. And, in terms of intimate relations, many felt they had to “catch up” for time lost, and became involved in turbulent relationships. They had to find their ways in a new social world, with unfamiliar faces, unwritten rules, and an unknown future.

Punishment serves various purposes: Deterrence, incapacitation, retribution, and rehabilitation. One may argue that these long sentences are a way to protect society and provide retribution for the crimes that they have committed. In the status quo regarding punishment of lifers, however, the final aim of punishment – rehabilitation – seems to have been abandoned. This raises concerns regarding lifer re-entry, including the lifers whose sentence Obama is commuting: if, after all those decades, we attempt to find the key that we though had been thrown away, and do nothing in terms of rehabilitative efforts, these men and women have a low likelihood of succeeding with nothing but a bus ticket and a bag of clothes.

By providing them with proper tools such as education and support well after release, the vast majority of lifers have a chance of shedding their prison identity, and live crime-free, productive lives after release. Providing them a fair chance on the job market, re-entry support in a world long left behind, and adequate programming taking into account the prolonged period of confinement would enable these lifers to start a life beyond bars. Perhaps more fundamentally, we hope that our books emphasize the need for more sustained public debate about incarceration, and its effect on the people within it.

Marieke Liem is Senior Researcher and chair of the Violence Research Initiative at Leiden University and a Marie Curie Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School and the author of After Life Imprisonment: Reentry in the Era of Mass Incarceration (NYU Press, 2016).

Jan Banning is a photographer and the author of Law & Order: The World of Criminal Justice (Ipso Facto, 2015).