—Wendy L. Rouse

Women’s self-defense classes are often seen as a relatively recent phenomenon. Yet, the women’s self-defense movement has a much longer history that has paralleled the various waves of women’s rights. In fact, the origins of women’s self-defense emerged alongside the fight for the right to vote during the first wave of the women’s rights movement in the early twentieth century.

As a nationwide obsession with athletics took hold in the early twentieth century, the “manly art” of boxing was touted as a way of developing both character and physical strength in men. Perhaps unexpectedly however, boxing also rapidly became a popular fad among a new generation of politically empowered and socially active women and college girls as a means of exercise and self-defense. Some people objected to this trend on the grounds that boxing might masculinize women. One approach to this criticism was to focus on the wide range of health benefits associated with boxing. Newspaper articles patronizingly emphasized boxing’s ability to enhance feminine beauty and cure a “bad temper,” “feminine hysterics,” or a “catty disposition.”

Industrialization and urbanization increasingly drew women out into the public world for school, work, and leisure. Whereas previously the city streets were primarily considered the realm of men, women increasingly began to occupy public space. Their presence in traditionally male spaces faced backlash. Mashers (a slang term used to describe men who harassed or made unwanted sexual advances towards women in the city streets) and violent attacks against women quickly became topics of discussion in the nation’s newspapers. With women’s personal stories of harassment and sexual assault dominating the headlines of newspapers, law enforcement and the courts increasingly began to take these types of attacks very seriously. However, women discovered that the police were not always willing or able to protect them.

As women increasingly recognized that men were not their “natural protectors,” self-defense training offered women an opportunity to learn how to protect themselves. They rejected the notion of male protectionism and began to insist that women had the right and ability to be their own defenders. Thus, self-defense training became a highly appealing practice for more and more women.

American fear of Japanese military might and a fascination with Japanese culture in the early twentieth century, led to an interest in the martial art of jiu-jitsu. Critics initially condemned jiu-jitsu as a more feminine, less manly means of fighting. Although he believed Western wrestling and boxing were the superior manly arts, President Theodore Roosevelt recognized the advantages of jiu-jitsu as a fighting method and advocated for its adoption by the American military. This endorsement provided an opportunity for some middle- and upper-class white women to take up the Japanese art of self-defense.

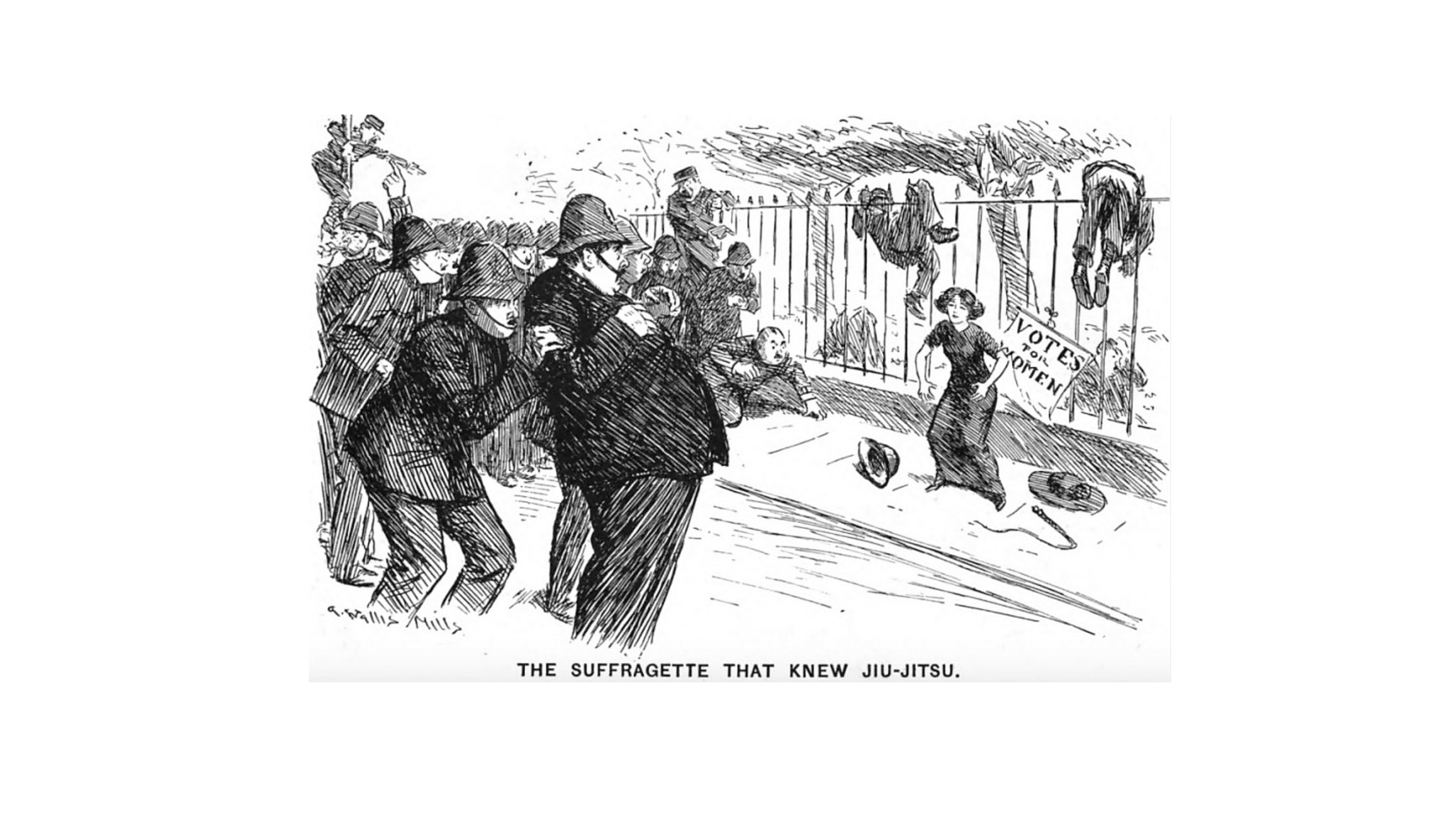

Women fighting for the right to vote in England faced intense police brutality and physical assaults from anti-suffragettes. Self-defense training took on an explicit political meaning as suffragettes studied jiu-jitsu to protect themselves against these violent attacks. Some American suffragists, inspired by the suffragettes across the Atlantic, likewise discovered the political implications of their physical empowerment through self-defense training. Cartoons such as this one reflect a broader uncertainty and anxiety about how to make sense of militant suffragettes who powerfully stretched the boundaries of acceptable feminine behavior.

The public discussions about street harassment and assaults against suffragists provided an opportunity for women’s rights activists to dispel myths about the actual sources of violence against women. A few prominent activists pointed out the radical truth: that women were most at risk for violence not from strangers on the street but from the men in their own homes. This reality further shattered the notion of men as women’s natural protectors and further inspired women to advocate the notion that women can and should be their own defenders. Representing a radically empowering idea of autonomy and personal defense, jiu-jitsu and boxing gave some women a sense of security and wellbeing within the domestic sphere.

As the first wave of the women’s rights movement waned in the 1920s, so too did the practice of women’s self-defense. The 1960s-1970s and the 1990s would witness the emergence of the second and third waves of feminism and the rebirth of a much broader women’s self-defense movement. These new self-defense movements were committed not only to the physical empowerment of women but to larger discussions about the realities of violence against women. Activists focused on dispelling the narrow emphasis on the dangerous stranger and looked instead at the multiple sources of harassment and violence that women encountered on the street, in their places of employment and in their homes. They also focused on challenging harmful gender stereotypes, a sexist patriarchal system, and a pervasive rape culture. Their fight continues to the present day.

Wendy L. Rouse teaches United States History and social science teacher preparation at San Jose State University. Her research interests include childhood, family, and gender history during the Progressive Era. She is the author of Her Own Hero: The Origins of the Women’s Self-Defense Movement (NYU Press, 2017).