— Miri Song

For many people, becoming parents can engender a re-evaluation of their own identities, and what they may (or may not) want to pass down to their children, including particular ethnic and cultural traits and practices. Such considerations about parenting and family transmission are often regarded as largely a matter of choice on the part of parents. However, such choices may be of particular importance for immigrants who have come from quite different societies, or for people who are in interracial unions. For instance, if a White American and Asian American individual had a child, they may choose to identify their child solely as White American, solely as Asian American, or as both White and Asian. But what happens when the child of this couple, who is (1st generation) multiracial, has children of her own? Would her (2nd generation multiracial) children encounter a similar set of ethnic and racial identity options for themselves? Does this further generational distance point to a corresponding decline in the attachment to one’s minority ancestry or ancestries?

Well, the answer is that we do not know what happens when we explore multiracial people a further generation down – that is, when multiracial people have children of their own. This is because there are no clear social conventions for how those (2nd generation multiracial) people should identify, or how they may be seen by others. Up to now, almost all studies of ‘mixing’ in North American and Britain have been premised upon unions involving ‘one race’ individuals, such as Black people, or White people with no known ancestors of another race. So when an interracial couple (e.g. Black and White) has a multiracial child, that child is often said to be half this, and half that, drawing on the well understood notion of racial fractions.

Racial fractions can, of course, divide even further, in the case of the children of multiracial individuals – e.g. someone may be described as a quarter X or a quarter Y. But what is fascinating about looking down the generational pipeline is that there is no easy way to predict how or why particular multiracial people may identify (and raise) their children in specific ways. This is because there are so many factors which come into play: What is the specific racial mix of the multiracial parent? What does the child look like? Where does the family live – in a predominantly White suburb or a diverse metropolitan area? How did the multiracial parent of the child relate to his or her own ethnic and racial ancestries? What are the ethnic and racial backgrounds of the multiracial parent’s spouse (that is, the other parent)? And so on….

Furthermore, two people with the exact same multiracial backgrounds (Black and White), and with partners of the same racial backgrounds (White), can still identify and raise their children in quite different ways. For instance, it is fully possible that couple A, who live in a mostly White suburb, may tell their child that they are White, while couple B, who live in an area with many more Black people, may decide that their child should identify as, and be seen as, multiracial. Moreover, the importance of race, and concerns about racism, can vary significantly across the multiracial population.

Since there is no one typical narrative about the meanings and significance of minority ancestries for the multiracial individuals in this study, Multiracial Parents explores the various ways in which they have thought about their status and experiences as mixed people, as well as how they identify and raise their children. An investigation into the experiences of multiracial people and their families is highly topical, as mixed people and unions are increasingly common in many parts of Britain—as well as other highly diverse societies such as that of the United States. Increasingly, the dynamics of multiracial identity and experience are central to family life and the shifting boundaries of race in the 21st century.

Miri Song is Professor of Sociology at the University of Kent. She is the author of Multiracial Parents: Mixed Families, Generational Change, and the Future of Race (NYU Press, 2017) and Global Mixed Race (NYU Press, 2014).

Miri Song is Professor of Sociology at the University of Kent. She is the author of Multiracial Parents: Mixed Families, Generational Change, and the Future of Race (NYU Press, 2017) and Global Mixed Race (NYU Press, 2014).

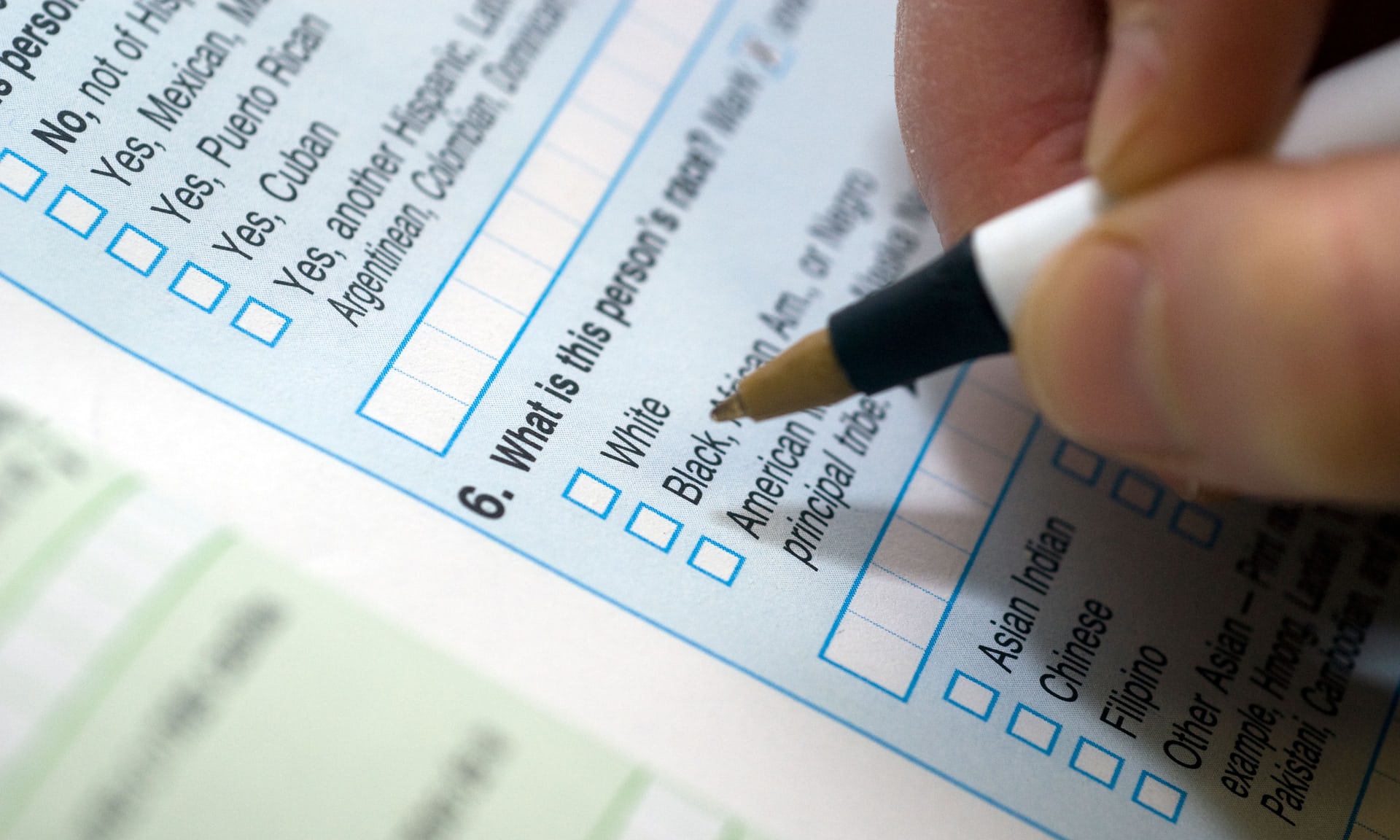

Featured Image: Alamy Stock Photo