—Erika Gasser

For Halloween enthusiasts like myself, the entire month of October offers an opportunity to enjoy classic horror films and to plan costumes and decorations. And in Salem, Massachusetts, the site of America’s most infamous witchcraft trials in 1692-1693, the entire month is dedicated to “Haunted Happenings”—a multifaceted Halloween festival that can be as entertaining for visitors as it can be trying for locals. The festival rests on the uneasy relationship between the history of the witchcraft prosecution that originated in Salem Village (now Danvers), Salem Town, and spread throughout Essex County near the end of the seventeenth century, on the one hand, and more modern images of witches that often bear little resemblance to their suspected historical counterparts. But whatever one thinks of “Haunted Happenings” its popularity demonstrates the depth of the nation’s preoccupation—notably reinforced by Arthur Miller’s The Crucible (1953)—with the idea of historical witchcraft as a lens through which to understand ourselves. It is hard to resist the urge to find a stable truth about “what really happened” in 1692, especially if that truth allows us to draw conclusions that feel pertinent to our ongoing preoccupations with the potential for abuses of official power. There are so many invoked Salems in popular and social media that it can be difficult for the historical subjects of 1692 to remain squarely in focus for very long.

In my recent book with NYU Press, Vexed with Devils: Manhood and Witchcraft in Old and New England, I follow in the footsteps of many historians who have tried to understand Salem according to a particular set of questions. But rather than attempt to argue for one among various possible causes for the outbreak, I emphasize the ways that witchcraft in Salem—which in several ways was atypical—nonetheless represented considerable continuity with English cases that emerged across the long seventeenth century. In addition to studying published cases of witchcraft, I consider related instances of what I call witchcraft-possession: cases in which afflicted persons acted out some of the stylized symptoms of demonic possession but also named a human intermediary as the cause. Furthermore, by focusing on manhood in a phenomenon that was overwhelmingly associated with women, I sought to determine the extent to which a gendered analysis might continue to offer new insights about the way power was wielded in these complex circumstances. Ultimately, I found that manhood mattered a great deal for individuals of both sexes who acted as if they were possessed, for men accused of being witches by the possessed, and men who published possession propaganda; gender’s inconsistent but pervasive influence helps to reveal the persistence of patriarchy, that principle for the organization of power to which both transatlantic societies remained committed.

Consider for example the downfall of the Reverend George Burroughs who, because of his sex and potential claim to religious authority, was one of the most infamous of those executed for witchcraft in 1692. Historians like Bernard Rosenthal and Mary Beth Norton have uncovered many fascinating aspects of Burroughs’s case that likely contributed to his downfall, from his suspect religious orientation to his connections to military disasters on the Maine frontier. Many have also noted his boasting and cantankerous nature, and the accusations that he was cruel to his wives. Female accusers who performed some of the symptoms of possession reported that apparitions of those dead wives appeared in their winding sheets (shrouds) to report that he had murdered them, looking very “red and angry” at Burroughs as they cried out for vengeance. Male accusers, who did not see apparitions or otherwise act as if possessed, relayed how Burroughs had boasted of knowing more than was revealed to most, and had demonstrated what seemed to be preternatural strength for one of his stature. Both sets of accusations served to strengthen the case against Burroughs, which some ministers viewed as particularly, even overwhelmingly, strong. But we can also see that the testimony from both sets of accusers presented Burroughs as failing to embody a proper manhood because he showed a deficiency of some key qualities, such as husbandly care, and an excess of others, notably knowledge and strength. I argue that Burroughs was “unmade” as a man and into a witch because of these excesses and deficiencies, which is not quite the same as claiming that his conviction indirectly or implicitly feminized him.

The question of the pervasive association of witchcraft with womanhood ought to remain in our minds, however, even when discussing men who were executed for the crime. We need to keep both women and men in view during these unusual but revealing moments of crisis because their downfalls each contribute to our understanding of how gender’s flexibility allowed it to be invoked by all parties in conflicting ways. Ultimately, it was power that determined the fates of those accused in England and New England, and so for that reason it does appear to make sense that we continually look to witchcraft trials to tell us something about our current fears. Entertainment aside, the harrowing experiences faced by the historical suspects serves as a reminder of humans’ capacity to pursue enthusiastically the condemnation and execution of those we fear. To recognize this potential in ourselves and to grapple with its implications is truly the scariest thing about the season.

Erika Gasser is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Cincinnati and the author of Vexed with Devils: Manhood and Witchcraft in Old and New England (NYU Press, 2017).

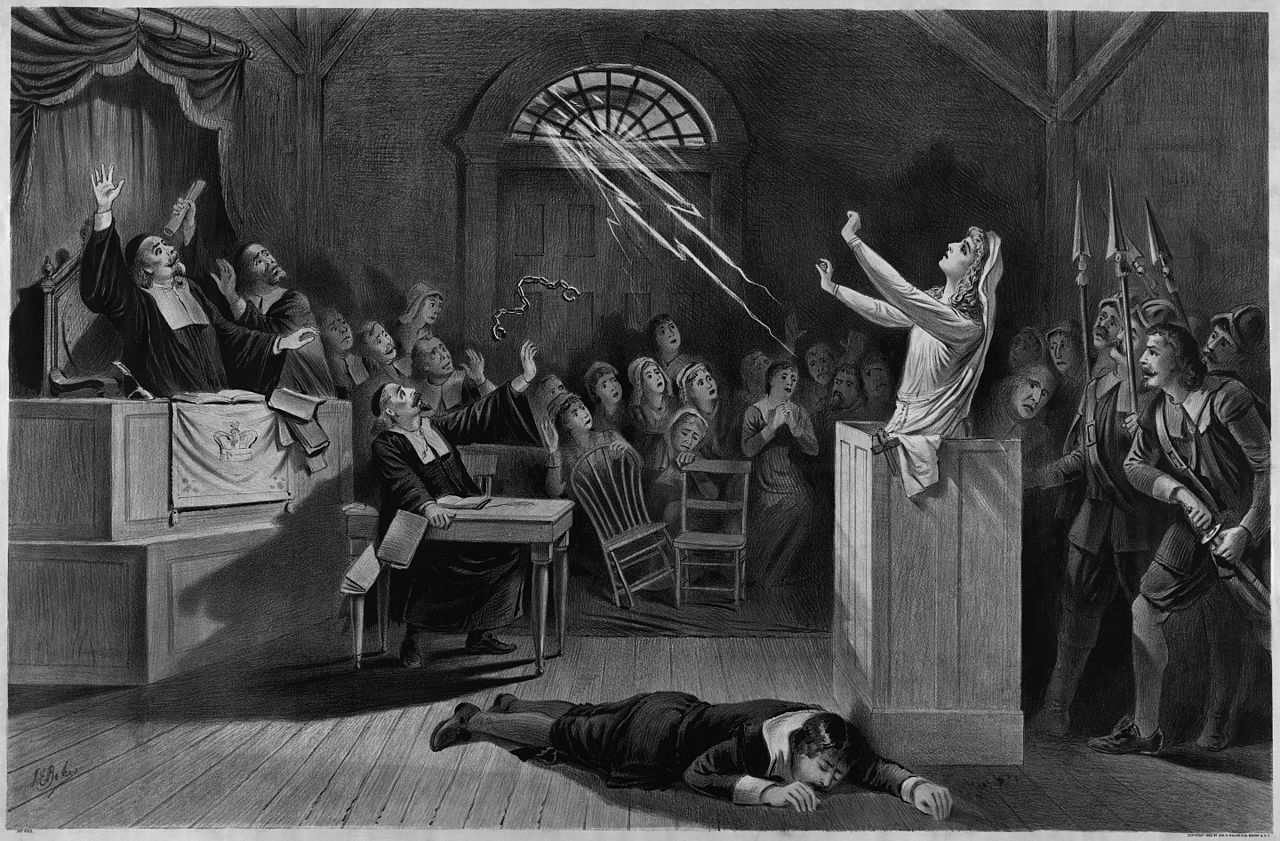

Featured Image: By Baker, Joseph E., ca. 1837-1914, artist. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons