—Gerald Horne

“Resistance” is the buzzword du jour in light of the incoming U.S. administration led by Donald J. Trump.

Already, there have been massive protests—including the historic “Women’s Marches” that rocked Washington, D.C. in particular. (My sources tell me that the march in Los Angeles—believe it or not—was even larger than the one that engulfed the capital.)

Apparently there is at least adequate follow-up too.

Still, I think those concerned about the current direction of this nation would do well to study extensively the history of a segment of this population, who had once a mantra in the bad old days of slavery that concluded forcefully, “Let Your Motto be Resistance.”

What I mean is that those whose very presence and existence belied easy notions of this republic being a supposed citadel of “liberty” and “freedom” now present a case study of how to push back against oppressors: I speak, of course, of African-Americans.

And the central lesson of African-American history is that the key to resistance is lengthening the battlefield, not relying solely or wholly on domestic allies—as important as they might be in the short term.

During the pre-1776 colonial era in North America, enslaved Africans often allied with Spain against Britain, not least since Madrid from the 1500s often armed Africans in order to combat European rivals, e.g. London to the point that there were those that felt it was not accidental that English speakers routinely referred to Africans by using the Spanish word for “black”, i.e. “Negro,” as if Africans were defined inherently as being much more than linguistic allies of His Catholic Majesty in Madrid.

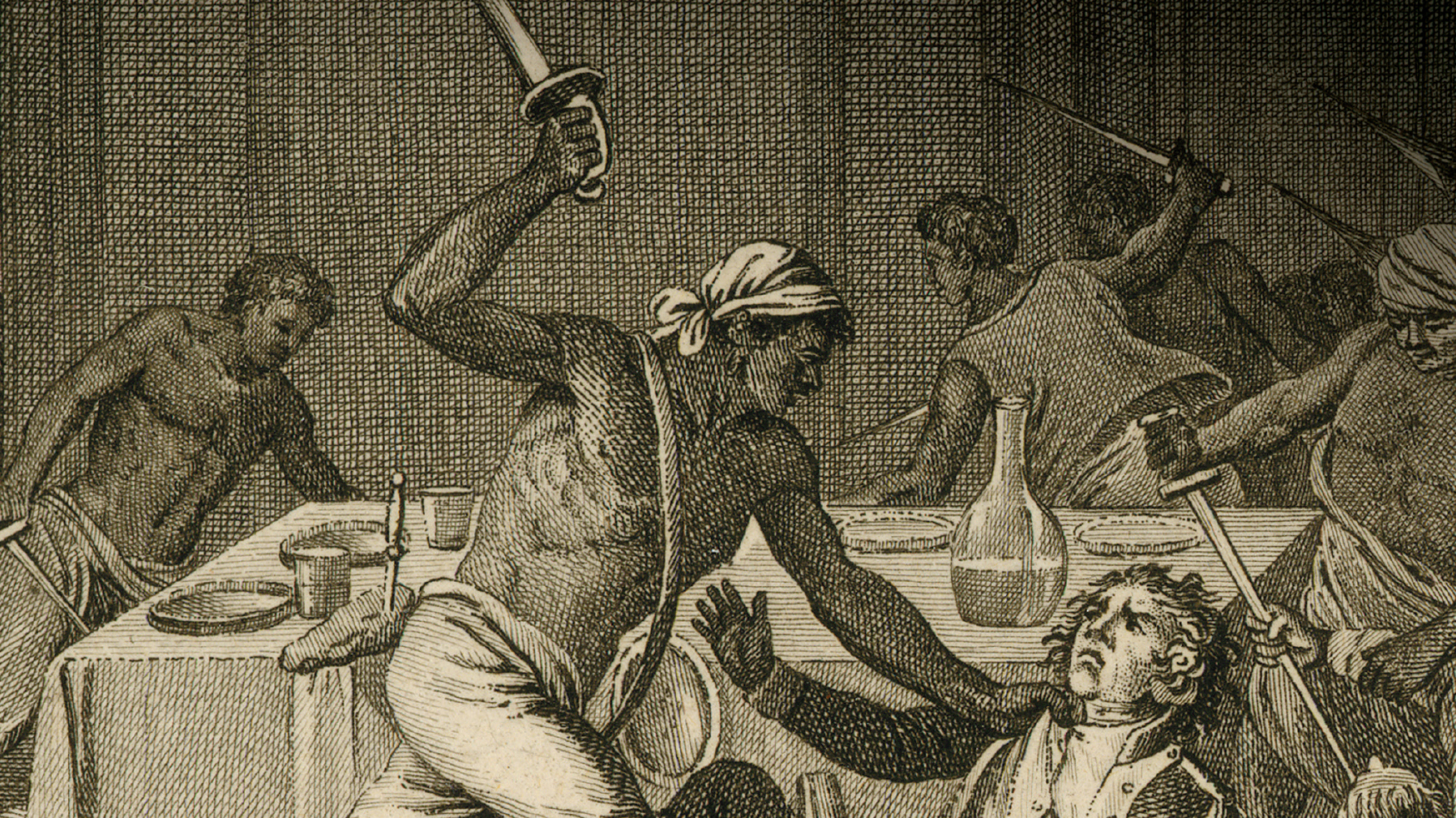

Then when the European settlers in North America revolted against London—not least because there was a widespread perception among Africans that George Washington and his comrades were determined to perpetuate slavery forevermore in the face of a 1772 decision in Britain that illegalized the “peculiar institution” at least in England, Africans supported the redcoats by several orders of magnitude. Thus, 1776 could be characterized easily as a “counter-revolution” against the promise of abolitionism as much as anything else.

“Resistance” meant fighting the settlers but, alas, the latter triumphed and, thus, one explanation of why and how African-Americans have been treated so atrociously is simply because when one fights a war and loses, expect to be punished and penalized indefinitely—and this includes one’s descendants too.

Nonetheless, after the proclamation of the U.S., Africans continued to ally with London, to the point where they were described as “Negro Comrades of the Crown”. This included helping the redcoats torch Washington, D.C. in August 1814, sending President James Madison and his garrulous spouse, Dolly, fleeing into the streets one step ahead of the posse.

After this global pressure caused the U.S. to make an agonizing retreat from slavery in 1865, resistance for African-Americans meant allying with revolutionary Mexico in the first few decades of the 20th century and, for certain Black Nationalists, allying with Tokyo in the pre-1945 era.

Resistance also meant allying with the Communist International, as exemplified by Shirley Graham Du Bois, better known as the spouse of W.E.B. Du Bois, who has been “blamed” or given credit (depending on one’s viewpoint) for his recruitment to the ranks of the U.S. Communist Party. As a number of historians have acknowledged to the point where it has become common wisdom, Washington found it difficult to point the finger of accusation at Moscow for human rights violations as long as Jim Crow stained the national escutcheon. Jim Crow had to go as a result—and this was the direct outgrowth of a well-conceived global plan of resistance that included the likes of Shirley Graham Du Bois.

Thus, with Donald Trump receiving about 58% of the votes of those defined as “white” (along with about 53% of the women of this group), an uphill climb awaits those who plan to resist the White House’s diabolical plans solely in the domestic arena. Fortunately, the historic “Women’s Marches” of 21 January 2017 were not just national but international, taking place globally.

Fortunately still, African American history provides a textbook for resistance and points in a similar direction: that is, to be effective in the U.S., resistance—dialectically—must be global.

Gerald Horne is Moores Professor of History and African-American Studies at the University of Houston. His books include The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America (NYU Press, 2014), Negro Comrades of the Crown: African Americans and the British Empire Fight the U.S. Before Emancipation (NYU Press, 2012), Race War!: White Supremacy and the Japanese Attack on the British Empire (NYU Press, 2003), and Race Woman: The Lives of Shirley Graham Du Bois (NYU Press, 2002).

Gerald Horne is Moores Professor of History and African-American Studies at the University of Houston. His books include The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America (NYU Press, 2014), Negro Comrades of the Crown: African Americans and the British Empire Fight the U.S. Before Emancipation (NYU Press, 2012), Race War!: White Supremacy and the Japanese Attack on the British Empire (NYU Press, 2003), and Race Woman: The Lives of Shirley Graham Du Bois (NYU Press, 2002).