—Leah Perry

When 2016 Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump announced his run for presidency, after asserting that the U.S. had become a “dumping ground for everybody else’s problems,” he stated, “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best […] They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.” And thus began his presidential campaign of flagrant racism, nativism, and misogyny; he reiterated his message of fear-mongering and hatred in his “big” immigration speech on August 30, 2016: He brought out family members of citizens killed by “criminal aliens” to emphasize his desire to protect “Americans”…with a massive border wall that he would force Mexico to finance, mass deportation and punishment, and an end to amnesty. Trump launched and built his campaign platform in this “nation of immigrants” on racism and xenophobia towards Mexican immigrants, Latina/os, and Muslims. That racism and xenophobia continues to garner voter support even as many powerful Republicans—in most cases politicians who have worked assiduously to restrict women’s reproductive rights—denounced him after a video of him boasting about sexually assaulting women and which has been followed by numerous allegations of sexual assault surfaced. This was not, however, any sort of progressive move; as CNN political commentator Symone D. Sanders stated on Twitter to the tune of 59.7K likes and 40.7 retweets (at the time of writing), “You apparently can say whatever you want about Mexicans, Hispanics & Black people, but the Republican Party draws the line on white women.” There are also those pundits who have been consistently incredulous that a man who so openly advocates racism, sexual assault, and violence is a major-party candidate for president in 2016. This position too is problematic, and racism, nativism, and misogyny are not, as the Republican Party seems to suggest, separate issues nor are they issues of the past. Although he may seem like an over-the-top anomaly, Trump’s racist, sexist, violent anti-immigration rhetoric actually developed from bipartisan immigration discourse established in the 1980s, in response to the civil rights and “second-wave” feminist movements. The way that immigration was talked about from the congressional floor to popular culture in the 1980s and 1990s reveals how and why 1980s immigration was a crucial ingredient in the cohesion of the neoliberal idea of democracy, and created a legacy that Trump epitomizes.

Many celebrate the Reagan Era, when neoliberalism was cohering, as a “great” time when America was increasingly inclusive and prosperous. In truth, neoliberalism—and its inherent gender and racial violences—solidified in the 1980s with the dismantling of the welfare state. Neoliberalism’s simultaneous appropriation of multicultural and feminist discourses and deployment of ostensibly color and gender-blind appeals to protect (certain) citizens from crime and criminals either concealed or rationalized those violences. Grace Hong pointed out that “neoliberalism is a structure of disavowal…it claims that protected life is available to all and that premature death comes only to those whose criminal actions and poor choices make them deserve it.”1 In other words, neoliberal ideology tells us that everyone is invited to be safe and partake of capitalist goodies. If you are poor, incarcerated, or experiencing any sort of oppression or violence—if some lives seem to matter less than others—it’s not the result of an unequal system, because feminism and the civil rights discourse fixed inequality. Instead, it’s your fault or, sometimes, it is the fault of one individual perpetrator. Neoliberalism also deploys race and gender-neutral appeals to protect (certain) citizens from crime and criminals. For instance there is a common assertion that immigration restriction is not about Muslims, it’s about terror; mass deportation is not about Mexicans but rather, it’s about “illegal aliens” murdering American citizens. Both neoliberal uses of feminist and multicultural ideas mitigate or rationalize everything from the dismantling of the welfare state to increasingly punitive laws, to the erection of a border wall, to the murder of unarmed black men and women. The way we talked about immigration in the 80s and 90s was central to how this neoliberal idea of democracy, which circulates in pop culture and is implemented in policy and policing, came to be. My work is about how the nexus of gender, race, and immigration structure neoliberalism, and suggests that immigration politics are far more important than they may seem.

***

We need to return to the 1980s to see this. Beginning with his election in 1980 and on the heels of an economic depression and widespread unemployment in the 1970s, Reagan set out to revolutionize America with deregulation of the economy, privatization, and the Cold War globalization of American capitalist democracy. He also needed to placate a polity suspicious of the government after Vietnam and Watergate, and given the victories of the civil rights and “second-wave” feminist movements, politicians could not appear to be racist and sexist and had to tolerate at least superficial gains for people of color and women. For his part, Reagan tokenized women and people of color as with his Supreme Court nominations of Sandra Day O’Connor and Clarence Thomas.2 At the same time, more direct backlash against civil rights and feminist advances came in opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment, affirmative action, and welfare, and via the “War on Drugs,” which Reagan blamed on Communist governments in Latin America and poor people of color in inner cities. These various forms of backlash were often coded in race-neutral appeals to protect “family values.”

At the same time, since the 1970s, pundits claimed that the country was having an illegal immigration crisis, but demographics were just shifting. U.S. policies such as the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965’s loosening of direct racial restrictions and emphasis on family reunification; a new Western Hemisphere quota; austerity measures in Latin America that necessitated migration despite that new quota; and the availability of domestic and service sector jobs led to increased immigration from Latin America, Asia, and the Caribbean, and many more women from these nations. How immigration was discussed and legislated, particularly with regard to Latin American, Asian, and

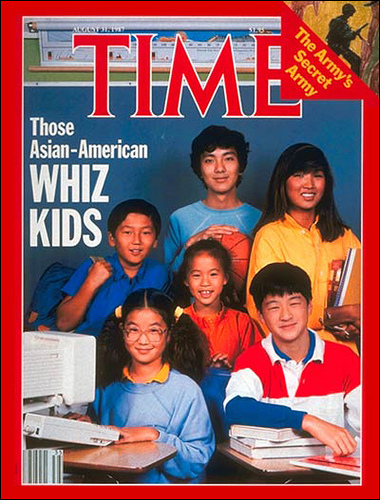

white ethnic immigrants, was transformed in ways that navigated these new tensions around race, gender, and the economy. J ust as the dehumanizing term “illegal alien” was becoming affixed to Mexicans and Latina/os in general, the quintessential American success story became that of the white ethnic immigrants (that is, immigrants of Irish and eastern and southern European descent). According to this now standard “nation of immigrants” ideology, white ethnics arrived at the turn of the twentieth century and in the midst of poverty and discrimination created a better life for their families with nothing but hard work and plucky determination. Since these self-reliant immigrants earned access to American equal opportunity with nothing but hard work and “family values,” so too, the story went, could anybody. (That those immigrants were white and received enormous amounts of federal aid with policies such as the GI Bill and housing loans that were disproportionately denied to people of color was conveniently forgotten.) The “nation of immigrants” narrative, often framed as part of the mainstreaming of multiculturalism and feminism, was crucial to the United States’ appearance as a humanitarian haven in the context of the Cold War. It was also a new iteration of white supremacy in that it incorporated a few people of color—“model minorities”—if they contributed to the economy and had proper

ust as the dehumanizing term “illegal alien” was becoming affixed to Mexicans and Latina/os in general, the quintessential American success story became that of the white ethnic immigrants (that is, immigrants of Irish and eastern and southern European descent). According to this now standard “nation of immigrants” ideology, white ethnics arrived at the turn of the twentieth century and in the midst of poverty and discrimination created a better life for their families with nothing but hard work and plucky determination. Since these self-reliant immigrants earned access to American equal opportunity with nothing but hard work and “family values,” so too, the story went, could anybody. (That those immigrants were white and received enormous amounts of federal aid with policies such as the GI Bill and housing loans that were disproportionately denied to people of color was conveniently forgotten.) The “nation of immigrants” narrative, often framed as part of the mainstreaming of multiculturalism and feminism, was crucial to the United States’ appearance as a humanitarian haven in the context of the Cold War. It was also a new iteration of white supremacy in that it incorporated a few people of color—“model minorities”—if they contributed to the economy and had proper  “family values.” This created the illusion of a level playing field and granted people of color humanity only in so far as they played by the neoliberal rules.

“family values.” This created the illusion of a level playing field and granted people of color humanity only in so far as they played by the neoliberal rules.

In 1980s popular media, which most Americans encounter and engage with before policy debates, national inclusion was framed as multicultural and sometimes feminist, giving rise to a spate of popular new TV shows and films that featured lovable white ethnic immigrant characters. We have Italian Americans Sophia Petrillo (Golden Girls) and Tony Micelli (Who’s the Boss?), and Balki Bartokomous, who emigrated to Chicago from the fictional Mediterranean island of Mypos (Perfect Strangers). There were spectacles like the celebration of America as the “mother of exiles” at the Statue of Liberty centennial in 1986. On July 4, 1986, Reagan pressed a button shooting a laser beam across the harbor to symbolically reignite Lady Liberty’s torch. The largest firewo rks display to date followed, set to “Stars and Stripes Forever,” and Chief Justice Warren Burger swore in newly naturalized citizens at Ellis Island while four simultaneous ceremonies took place nationwide.3 Neil Diamond sang his popular song, “Coming to America” which contains the rousing chorus, “Everywhere around the world/They’re coming to America/Every time that flag’s unfurled/They’re coming to America.” News media also positioned the United States as the exceptional nation where women from patriarchal cultures—often in the “third world”—could be liberated. White ethnics modeled this, like the “empowered” “Material Girl” Madonna. The 1990s saw the opening of the Ellis Island Museum and the Latinization of American pop culture, epitomized by the rapid rise of stars such as U.S.-born Latinas Selena and Jennifer Lopez, which showed what was available to and for worthy immigrants (though neither is an immigrant.)4 The circle of national inclusion seemed to continue to broaden.

rks display to date followed, set to “Stars and Stripes Forever,” and Chief Justice Warren Burger swore in newly naturalized citizens at Ellis Island while four simultaneous ceremonies took place nationwide.3 Neil Diamond sang his popular song, “Coming to America” which contains the rousing chorus, “Everywhere around the world/They’re coming to America/Every time that flag’s unfurled/They’re coming to America.” News media also positioned the United States as the exceptional nation where women from patriarchal cultures—often in the “third world”—could be liberated. White ethnics modeled this, like the “empowered” “Material Girl” Madonna. The 1990s saw the opening of the Ellis Island Museum and the Latinization of American pop culture, epitomized by the rapid rise of stars such as U.S.-born Latinas Selena and Jennifer Lopez, which showed what was available to and for worthy immigrants (though neither is an immigrant.)4 The circle of national inclusion seemed to continue to broaden.

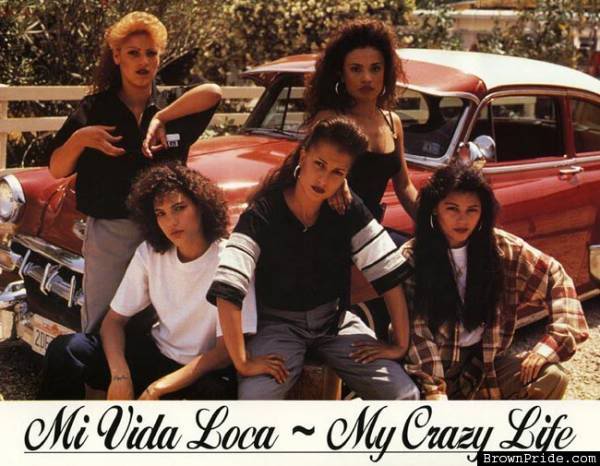

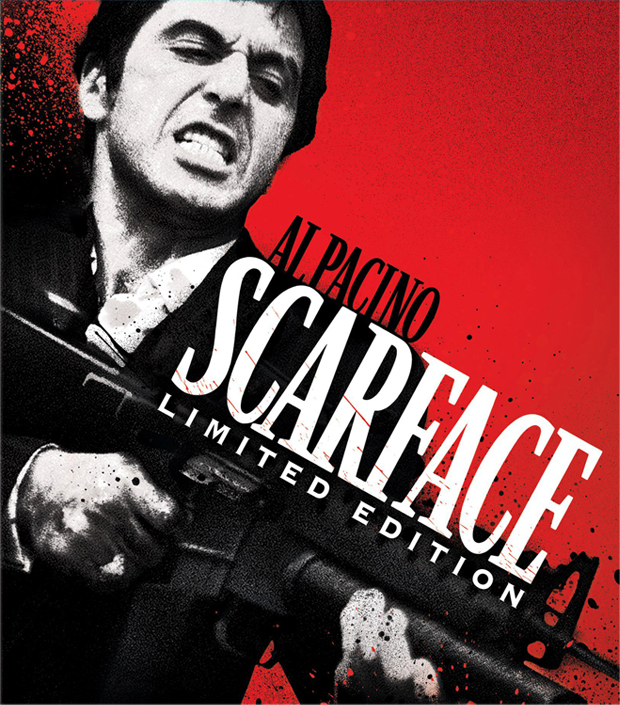

But when non-white immigrants deviated from the dominant value system—like ostensibly fecund, teenaged welfare-abusing Mexican American mothers in the film Mi Vida Loca (1994) or criminally inclined Cuban refugees, like the hyperviolent Tony Montana, antihero of Scarface (1983) or the numerous Latino drug dealer characters in a host of 1980s and 1990s films and TV shows, such as Colors (1988) and Miami Vice (1984-1990), they were rendered undeserving of everything from social services to residence in the United States, to even life itself. Recurring stories about immigration on the congressional floor and in popular media indicated that punishing legal action (like border militarization, welfare cuts, and the criminalization of undocumented entry) was not racist or sexist, but necessary to protect the economy and citizens.

But when non-white immigrants deviated from the dominant value system—like ostensibly fecund, teenaged welfare-abusing Mexican American mothers in the film Mi Vida Loca (1994) or criminally inclined Cuban refugees, like the hyperviolent Tony Montana, antihero of Scarface (1983) or the numerous Latino drug dealer characters in a host of 1980s and 1990s films and TV shows, such as Colors (1988) and Miami Vice (1984-1990), they were rendered undeserving of everything from social services to residence in the United States, to even life itself. Recurring stories about immigration on the congressional floor and in popular media indicated that punishing legal action (like border militarization, welfare cuts, and the criminalization of undocumented entry) was not racist or sexist, but necessary to protect the economy and citizens.

Heated bipartisan policy debates that included both discourses about immigrants went on for five years until congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA), the first overhaul of immigration since the 1965 law. Free market economists supported increased immigration not for humanitarian reasons like some Democrats and activist groups, but because cheap immigrant labor was profitable. Organized labor worried about labor competition, and nativists charged that immigrants threatened the economy, culture, complexion, and safety of the United States. The Mariel Boatlift added a layer of urgency.

IRCA navigated all these variables, establishing a policy paradigm for neoliberal immigration. IRCA combined amnesty with welfare restriction, increased militarization of the Mexican border, and employer sanctions that protected the employers of undocumented workers. Amnesty was dressed up as an example of Reaganite “nation of immigrants” exceptional inclusivity, but this new program for temporary labor importation that was disproportionately granted to Mexican men was what Mae Ngai has called “imported colonialism.”5 The punitive provisions were framed as necessary for the safety of “Americans,” and as IRCA’s primary sponsor Senator Alan Simpson (R-WY), put it, “American people were ‘offended’ by an immigration and refugee policy that made them the ‘sugar daddies of the world.’”6 He cast immigrants as feminized burdens that drained the masculinized national polity, and while Simpson’s phrasing was unique, he was by no means the only pundit who coupled misogyny and immigration policy. Gender was a constant underlying theme, even in debates that were ostensibly over other issues, and certainly in the implementation of the law.

IRCA navigated all these variables, establishing a policy paradigm for neoliberal immigration. IRCA combined amnesty with welfare restriction, increased militarization of the Mexican border, and employer sanctions that protected the employers of undocumented workers. Amnesty was dressed up as an example of Reaganite “nation of immigrants” exceptional inclusivity, but this new program for temporary labor importation that was disproportionately granted to Mexican men was what Mae Ngai has called “imported colonialism.”5 The punitive provisions were framed as necessary for the safety of “Americans,” and as IRCA’s primary sponsor Senator Alan Simpson (R-WY), put it, “American people were ‘offended’ by an immigration and refugee policy that made them the ‘sugar daddies of the world.’”6 He cast immigrants as feminized burdens that drained the masculinized national polity, and while Simpson’s phrasing was unique, he was by no means the only pundit who coupled misogyny and immigration policy. Gender was a constant underlying theme, even in debates that were ostensibly over other issues, and certainly in the implementation of the law.

Part of neoliberal restructuring is an increasing militarism and securitization at national borders as they become more permeable with transnational flows of capital and labor. Following IRCA’s passage, a steel fence was constructed along the Mexico–U.S. border, large-scale enforcement efforts such as Operation Blockade/Hold the Line (1993) in El Paso, Texas, and Operation Gate Keeper (1994) in San Diego, California were undertaken, more sophisticated technology was implemented, and the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS)’s budget and personnel were expanded again, with the number of border agents increasing from 3,693 in 1986 to 9,212 in 2000.7 New “control” efforts generated increasing fear of apprehension and persecution on the part of border-crossers, which was not unfounded, for the number of crossing-related deaths also grew: in 1994, 23 migrants died attempting to cross. After Operation Gatekeeper, there were 61 deaths in 1995, 89 in 1997, and 145 in 1998.8

Like the Texas Rangers, the newly beefed-up Border Patrol engaged in gendered brutality and rape as immigration control. A 1998 Amnesty International study found that women detained by the INS were subjected to degrading vaginal searches by male Border Patrol officers and were frequently sexually abused and assaulted. Women were pressured to remain silent; two women who complained were accused of lying.9 In reports filed between 1992 and 1997, Human Rights Watch found that sexual abuse was “rampant,” but although immigration agents were occasionally prosecuted for the rape of undocumented women, the crime was rarely reported.10 In addition to fearing law enforcement for obvious reasons, casting a woman as sexually deviant (because of her race or legal status or sexual behavior) renders her a criminal and un-rapable, a “logic” that erases systemic violence against women. Breaking immigration law and thus becoming an “illegal alien” likewise makes violence against one invisible, or rationalizes it.

These two conceptions of immigration—“nation of immigrants” and “immigration emergency”–surfaced repeatedly in relation to Latina/os, Asians, and white ethnics beginning in the Reagan years. In my work, I look at a range of sources, including legal documents, congressional debates, and popular media, to show that even while “multicultural” immigrants were embraced, they were at the same time disciplined through gendered discourses of respectability that continue to shape politics today, even with the added level of urgency that September 11, 2001 and the threat of “terror” brought to the forefront of immigration politics.

Racialized and gendered criminalization legitimates the framing of certain undocumented lives as lives that do not matter. It was highly effective because of its affective appeal in the Reagan era when the gains of “second-wave” feminism and multiculturalism threatened the beneficiaries of patriarchy and racism. Trump’s call to “build a wall” at the Mexican border because “they’re rapists”—while he has himself been accused of numerous sexual assaults—and current anti-refugee, anti-Muslim sentiment is the karmic fruit of 1980s immigration discourses in policy and pop culture. This is a direct pipeline, not an abnormality. In the 1980s the “immigration emergency” and “nation of immigrants” narratives became the standard for how we think and talk and pass laws about immigration, and that standard still creates and perpetuates violence against groups that are already vulnerable, creating the conditions for Trump to become a major-party presidential candidate. In order to change this, it is immigrant lives rather than legal status, cheap labor, a racist, sexist notion of “safety,” heteropatriarchal “family values,” contribution to the economy via hard work, box office hits, or cosmetic diversity that must be at the center of immigration reform.

- Grace Kungwon Hong, Death Beyond Disavowal: The Impossible Politics of Difference (Minneapolis: MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 17.

- Gil Troy, The Reagan Revolution: A Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 83.

- “Liberty Weekend Offers Full Schedule of Events,” Palm Beach Post, July 3, 1986, 7F, http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=J7VhAAAAIBAJ&sjid=R9sFAAAAIBAJ&pg=4397,1780677&dq=liberty-weekend&hl=en.

- Additionally, migration from/to Puerto Rico is a process that is related to but distinct from U.S. immigration in general, given Puerto Rico’s status as a former colony. The migration of Puerto Ricans to/from Puerto Rico and U.S. cities has been shaped by the state through projects such as the Chardon Plan and Operation Bootstraps, and gender significantly impacts Puerto Ricans’ migration experiences. See Gina M. Perez, The Near Northwest Side Story: Migration, Displacement, and Puerto Rican Families (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

- Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004).

- Quoted in Daniel J. Tichenor, Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002), 254.

- Joseph Nevins, Operation Gatekeeper: The Rise of the “Illegal Alien” and the Making of the U.S.–Mexico Boundary (New York: Routledge, 2002), Appendix F.

- Ibid., 145.

- Eithne Luibheid, Entry Denied: Controlling Sexuality at the Border (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), 121.

- Human Rights Watch, Brutality Unchecked: Human Rights Abuses along the U.S. Border with Mexico (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1992), 35, cited in Luibheid, Entry Denied, 121.

Leah Perry is Assistant Professor of Cultural Studies at SUNY-Empire State College. She is the author of The Cultural Politics of U.S. Immigration: Gender, Race, and Media (NYU Press, 2016).

Leah Perry is Assistant Professor of Cultural Studies at SUNY-Empire State College. She is the author of The Cultural Politics of U.S. Immigration: Gender, Race, and Media (NYU Press, 2016).